Regulatory Capture: How Industry Influence Undermines Public Protection

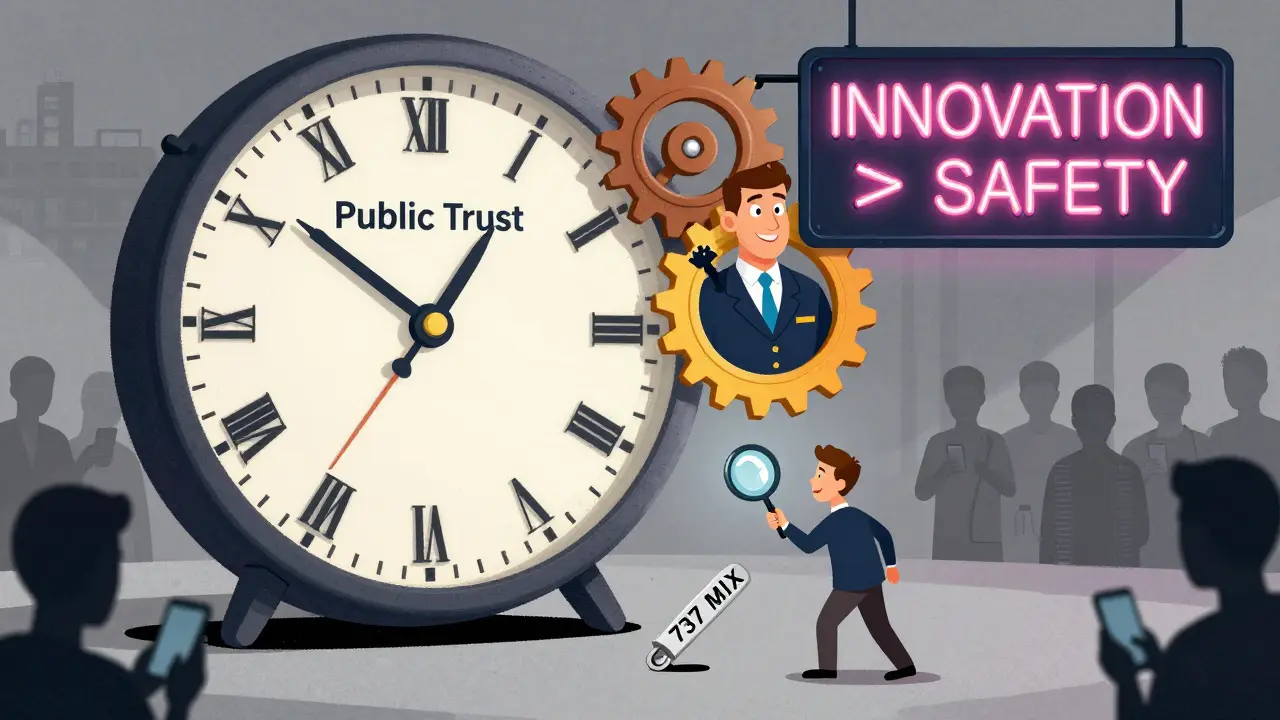

Every time you buy medicine, turn on your heat, or fly on a plane, you're relying on government regulators to keep you safe. But what happens when the people meant to protect you start working for the companies they’re supposed to be watching? That’s regulatory capture-and it’s not a theory. It’s happening right now, in plain sight.

What Is Regulatory Capture, Really?

Regulatory capture isn’t about bribery or shady backroom deals-though those happen too. It’s quieter, slower, and more dangerous. It’s when the agencies created to guard the public interest end up serving the industries they regulate. The regulators start thinking like the companies they’re supposed to control. They adopt their language, their priorities, their excuses. Over time, the rules bend. Enforcement slows. Safety gets traded for profit.

This isn’t new. The Interstate Commerce Commission was set up in 1887 to stop railroads from gouging farmers. By 1900, it was hiking rates at the railroads’ request. Fast forward to today, and you’ll see the same pattern: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approving drugs with weaker evidence than the EU, the Federal Aviation Administration letting Boeing employees review their own plane safety designs, and energy regulators approving billions in consumer bill hikes while letting companies keep profit margins far above legal limits.

The Two Main Ways Capture Happens

There are two main paths to regulatory capture: materialist and cultural.

Materialist capture is the obvious one. It’s the revolving door. Regulators leave their government jobs and take high-paying roles at the companies they once policed. A 2022 study found that 92% of former SEC commissioners joined regulated firms within 18 months of leaving office. The U.S. Department of Defense saw 53% of its top officials move into defense contractors within a year. These aren’t coincidences-they’re incentives. Why enforce strict rules if your next job depends on keeping the industry happy?

Cultural capture is harder to spot. It’s when regulators spend so much time talking to industry experts, attending their conferences, and relying on their data that they start seeing the world through their eyes. They think, “If this company says it’s safe, it probably is.” They worry about “stifling innovation” instead of “protecting lives.” They stop asking hard questions. A Harvard study found that capture often happens not through corruption, but through the slow alignment of professional identities. Regulators begin to see themselves as partners, not watchdogs.

Why It’s So Hard to Stop

Why don’t voters or politicians step in? Because the costs are hidden, and the benefits are concentrated.

Take the U.S. sugar industry. A handful of sugar producers get $1.2 billion extra in profits every year thanks to import tariffs. But those tariffs raise the price of sugar for every American household by about $33 a year. No one person feels it enough to protest. Meanwhile, sugar companies spend millions lobbying, donating to campaigns, and hiring former regulators. The public, spread thin across millions of people, doesn’t organize. The industry does.

There’s also the problem of information. Regulators don’t know how to monitor cryptocurrency, AI-driven drug trials, or complex derivatives. So they turn to the industry for help. The industry gives them data-filtered, incomplete, optimized for their own interests. Soon, the regulator can’t function without them. That’s not collaboration. That’s dependency.

And then there’s the system itself. In the U.S., companies can shop for the most lenient regulator. A pharmaceutical company might move its testing to a state with weaker oversight. An energy firm might pick a regional agency known for being “business-friendly.” This fragmentation makes accountability nearly impossible.

Real-World Consequences

The numbers don’t lie.

- The SEC missed warning signs before the 2008 financial crisis because 87% of its staff had ties to Wall Street firms.

- UK energy regulator OFGEM approved £17.8 billion in consumer bill increases while letting companies keep 11.2% profit margins-nearly double the legal limit.

- The FAA delegated 96% of safety reviews for the Boeing 737 MAX to Boeing employees. That led to 346 deaths.

- Public Citizen found that former EPA officials who joined fossil fuel companies caused a 28-day average delay in enforcement actions during their transition.

And it’s not just safety. It’s fairness. A 2023 Pew Research survey found 78% of Americans are deeply concerned about industry influence on regulators. On Reddit, users in r/politics linked high drug prices directly to FDA capture. On Yelp, financial service reviews average just 2.1 out of 5 stars-with 67% of negative comments blaming regulators for protecting banks, not customers.

Who’s Fighting Back?

Some places are trying to fix this.

Canada introduced mandatory “Regulatory Integrity Training” for officials. The result? Industry meetings got 27% shorter. Public consultations went up 43%. New Zealand rewrote its entire regulatory process to require independent reviews and forced industry panels to include consumer reps. Between 2016 and 2022, industry-preferred regulations dropped from 68% to 31%.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched a new “Regulatory Capture Initiative” in March 2023, creating an Office of Regulatory Integrity with a $23 million budget. The European Union now requires at least 40% consumer representation on advisory panels.

But these are baby steps. Between 2015 and 2022, 78% of proposed anti-capture laws in the U.S. failed. Lobbying spending by industries has grown 273% since 2020. And now, AI is making it worse. Companies are using bots to flood regulatory comment systems with 17,000 fake public comments per hour-making it look like millions support their position.

What Can You Do?

You might feel powerless. But you’re not.

First, know the signs. If a regulator never says no, if they always cite industry data, if their top officials keep landing jobs at the same companies they regulated-that’s not coincidence. That’s capture.

Second, demand transparency. Ask: Who advised this rule? Who wrote this regulation? Who’s on the advisory panel? Push for public disclosure of all industry contacts. Support organizations that track the revolving door.

Third, vote with your attention. Follow watchdog groups. Share stories like the Boeing 737 MAX or the sugar tariff. Public pressure is the only thing that can counterbalance industry money.

Regulatory capture doesn’t happen overnight. It’s built slowly, quietly, one meeting, one job offer, one ignored warning at a time. But it can be undone-by people who refuse to look away.

Is regulatory capture the same as corruption?

Not exactly. Corruption involves illegal acts like bribery or kickbacks. Regulatory capture is legal but unethical. It’s about influence, access, and culture. A regulator might never take a bribe, but if they leave their job to work for the company they used to oversee, and then soften rules to help that company-they’re part of the system of capture. It’s the slow erosion of public trust, not a single crime.

Which industries are most affected by regulatory capture?

The World Bank’s 2022 report shows the financial sector leads with 67% of countries reporting capture, followed by energy (58%) and pharmaceuticals (52%). These industries have high profits, complex rules, and powerful lobbying budgets. But it’s also happening in agriculture, tech, and even environmental agencies. Any sector where profits are concentrated and the public’s costs are spread thin is vulnerable.

Can regulators ever be truly independent?

Yes-but only with strong safeguards. Countries like New Zealand and Denmark have lower capture rates because they limit revolving doors, require public disclosure of all industry contacts, and mandate independent reviews. They also give regulators stable, non-political funding so they don’t have to beg for budgets from the very industries they regulate. Independence isn’t automatic. It’s designed-and defended.

Why do voters tolerate regulatory capture?

Because the harm is invisible. You don’t feel the $33 extra you pay for sugar each year. You don’t see the delayed drug approval or the ignored safety report. The costs are small for each person, but huge in total. Meanwhile, the benefits-lower prices, more jobs, innovation-are loud and clear. Politicians don’t lose votes over hidden costs. They lose votes over gas prices or drug bills. So they let regulators stay quiet.

What’s being done to fix this in 2025?

Several countries are testing new tools. The OECD now requires member states to conduct independent regulatory impact assessments by 2026. The EU mandates consumer representation on advisory panels. The U.S. FTC is tracking all industry contacts in real time. Some states are banning former regulators from working in their industry for five years. And citizen assemblies, like France’s Climate Convention, are giving ordinary people direct power to shape policy-bypassing industry lobbyists entirely. Progress is slow, but it’s happening.

Final Thought: The System Isn’t Broken-It’s Working As Designed

Regulatory capture isn’t a glitch. It’s the result of a system built to favor those with money, access, and influence. The regulators didn’t fail because they were bad people. They failed because the rules let them be shaped by the powerful.

Fixing it means changing the system-not just replacing a few officials. It means public funding for regulators. It means banning revolving doors. It means forcing transparency. It means giving ordinary people a real voice in rulemaking.

Until then, every time you hear a company say, “We’re working with regulators to ensure safety,” ask yourself: Who’s really in charge here?

It’s not just about regulators being corrupted-it’s about how we’ve built a system where the only way to get anything done is to speak the industry’s language. You don’t need a bribe if you’ve spent ten years at the same table, sharing coffee and jargon. The real tragedy? Most of these people started out wanting to do good.

It’s cultural erosion, not corruption. And it’s happening everywhere-from food safety to internet privacy. We think we’re protecting the public, but we’re just making the rules easier for the powerful to navigate.

Fixing it means breaking the cycle. Not just banning the revolving door, but rebuilding the culture around regulation. Public service should feel like a calling, not a stepping stone.

It’s hard to imagine a world where regulators don’t fear losing their next job. But that’s the only way trust comes back.

This is why we need independent oversight bodies funded by public trust, not industry cash. Real change starts with funding and structure, not just good intentions.

theyre all part of the deep state cabal. the fda, faa, sec-theyre all controlled by the globalists who want you dependent on their drugs and planes. you think its capture? its a takeover. the elites dont want you safe, they want you docile. and dont even get me started on the ai bots flooding comments-thats mind control tech right there. wake up.

so lets just ban all regulators from ever working in the private sector again right? and how about we fire every single one who ever went to a conference? this is why america is falling apart. nobody takes responsibility anymore. just blame the system. i worked in gov and i saw how hard it is to get anything done without industry input. you dont fix this by screaming you fix it by making people accountable not just pointing fingers

I’ve seen this up close in environmental permitting. Regulators aren’t evil-they’re overwhelmed. They’re given impossible mandates, zero training on new tech, and then expected to outsmart billion-dollar firms with PhDs on retainer. The problem isn’t malice. It’s design.

Canada’s training program? Brilliant. It’s not about distrust. It’s about rebuilding professional identity. If you teach people to see themselves as public servants first, not industry liaisons, the behavior changes.

And yes, we need to fund them properly. You can’t expect someone making $80k to say no to a $400k job offer from the company they used to regulate. That’s not corruption. That’s economics.

usa is the joke. look at australia-we’ve got the energy sector under control because we dont let lobbyists write the rules. you think your faa is independent? ha. our cdc would never let a company review its own safety data. you guys are so soft on power. and dont even get me started on how you let banks run your economy. its pathetic.

you say regulatory capture but you ignore that most regulators are just lazy bureaucrats who dont want to deal with the complexity. the industry gives them the answers because nobody else will. its not conspiracy its incompetence. also the 737 max crash wasnt capture its poor management and bad engineering. blame boeing not the faa. and dont act like the eu is some moral beacon-theyre just slower and more bureaucratic

They don’t need bribes. They just need to believe the industry’s narrative. That’s the scariest part. When you stop seeing your job as protecting people and start seeing it as enabling progress, you’ve already lost. I worked in public health. I saw it happen. One day, the regulator says, ‘We’re not going to block this because it’s too disruptive.’ And you realize-they’re not on our side anymore. They’re on the side of the status quo. And the status quo is profitable.

It’s not about one bad decision. It’s about a thousand small compromises. You don’t wake up corrupted. You wake up indifferent.

Just read the comments section of any regulatory proposal. 90% are from bots or industry reps. The real people? They’re too busy working two jobs to care. The system isn’t broken. It’s optimized for silence.