Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia: How to Recognize and Manage This Hidden Pain Trap

Imagine taking more opioids to control your pain-only to feel it get worse. Not just a little worse. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) makes your body more sensitive to pain, even as you increase your dose. It’s not tolerance. It’s not your original injury flaring up. It’s your nervous system turning up the volume on pain signals because of the very drugs meant to silence them.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

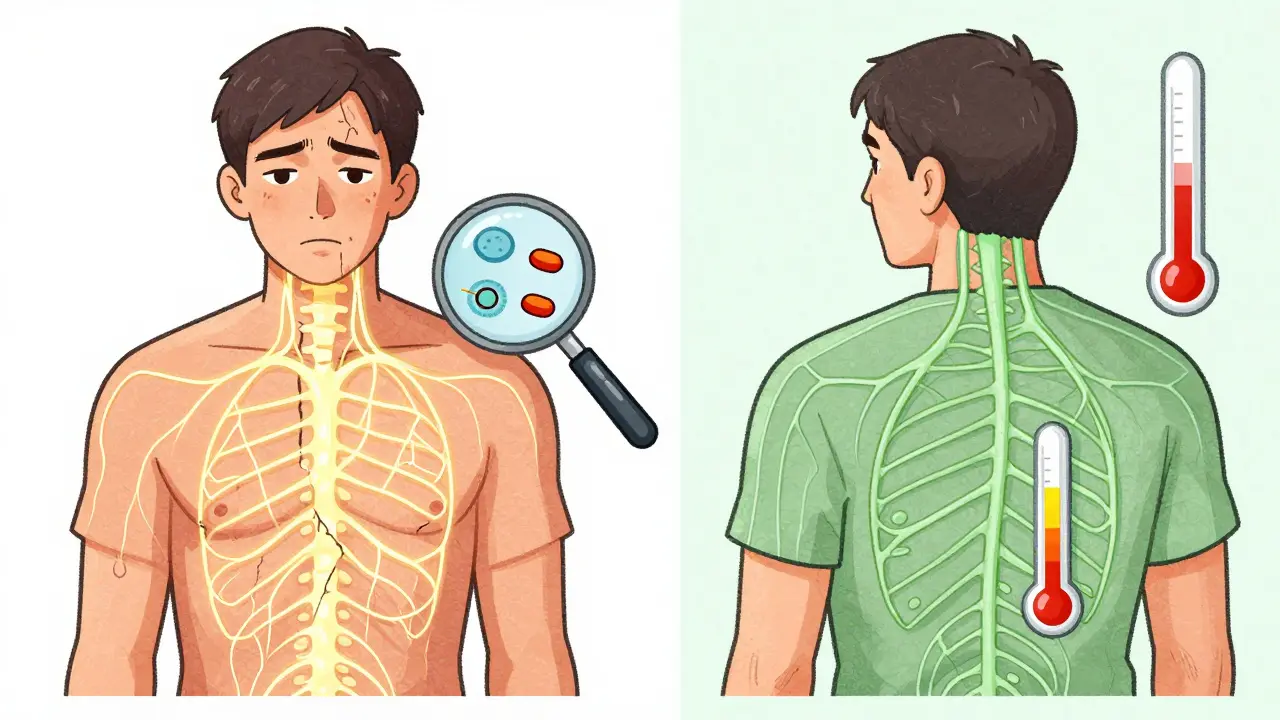

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia isn’t a myth or rare side effect-it’s a real, measurable neurobiological shift. First observed in lab rats in 1971, it’s now confirmed in humans: long-term opioid use can make your body more, not less, sensitive to pain. You might start with back pain or arthritis, but over time, even light touches, cold air, or a routine physical exam start hurting more than before. This isn’t anxiety or exaggeration. It’s your spinal cord and brain rewiring themselves in response to opioids.

Unlike tolerance-where you need higher doses to get the same pain relief-OIH means your pain gets worse when you increase the dose. You might notice your pain spreading beyond the original area. A knee injury might now cause burning in your foot. A headache might turn into full-body sensitivity. That’s allodynia: pain from things that shouldn’t hurt at all. It’s a red flag.

Who’s at Risk?

OIH doesn’t hit everyone, but certain patterns make it more likely:

- People on high-dose opioids-especially over 300 mg of morphine per day or equivalent

- Those using IV or long-acting opioids like hydromorphone or fentanyl

- Patients with kidney problems, where opioid metabolites build up

- Individuals on opioids for more than 2-8 weeks continuously

It’s not just about dose. Genetics matter too. Some people have variations in the COMT gene, which affects how their bodies process pain signals. These individuals are more prone to developing OIH, even on moderate doses. Studies show OIH affects 2-15% of chronic opioid users-but experts believe it’s underdiagnosed. Up to 30% of cases once labeled as "tolerance" may actually be OIH.

How Is It Different From Tolerance or Withdrawal?

This is where things get tricky. All three-tolerance, withdrawal, and OIH-can look similar: more pain, higher doses, frustration. But the clues are there.

Tolerance means you need more opioid to get the same relief. Your pain stays in the same place. You don’t feel new types of pain.

Withdrawal comes when you cut back or miss a dose. You get sweating, nausea, anxiety, muscle aches. Pain improves when you take the next pill.

OIH is the opposite. Pain gets worse after you take the opioid. The pain spreads. You develop allodynia. And if you reduce the dose? The pain often improves. That’s the biggest clue.

One patient I worked with had been on oxycodone for 18 months for a herniated disc. Her pain had been stable-until her dose was doubled. Then her entire leg started burning. Even brushing her hair hurt. She wasn’t withdrawing. Her spine wasn’t getting worse. Her pain was reacting to the drug itself.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

There’s no single blood test. OIH is diagnosed by ruling everything else out. Your doctor will check for new injuries, infections, nerve damage, or cancer progression. They’ll ask about your pain pattern: Is it spreading? Does it hurt more after a dose? Do you feel pain from light touches?

Some clinics use the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ), a validated tool with 85% accuracy in spotting OIH. Others use quantitative sensory testing-measuring how sensitive your skin is to heat, pressure, or cold before and after opioid use. If your pain threshold drops after taking opioids, that’s a strong indicator.

But here’s the catch: many doctors still don’t know to look for it. A 2024 survey found only 65% of pain specialists routinely consider OIH when patients report worsening pain. That’s improving, but slowly.

How Is OIH Treated?

The worst thing you can do is keep increasing the opioid dose. That makes OIH worse.

The first step? Reduce the opioid. Not stop. Not quit cold turkey. Reduce by 10-25% every 2-3 days. It’s slow, but it works. Many patients see improvement within 2-4 weeks. Full relief can take 4-8 weeks.

Switching opioids can help. Methadone is often effective because it blocks NMDA receptors-the same ones involved in OIH. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, also has a lower risk of triggering hyperalgesia.

Then there are targeted medications:

- Ketamine (low-dose IV or nasal): Blocks NMDA receptors. Studies show it can reverse OIH in days.

- Clonidine: An alpha-2 agonist that calms overactive pain signals in the spinal cord.

- Gabapentin or pregabalin: These help with nerve-related pain and central sensitization.

Non-drug approaches are just as important. Physical therapy helps retrain your nervous system. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches you how to respond differently to pain signals. Mindfulness and graded movement can reduce the brain’s amplification of pain.

Why Is This Still Overlooked?

Because it’s counterintuitive. Doctors are trained to think: more pain = need more opioid. It’s a reflex. OIH flips that logic. It requires stepping back, questioning assumptions, and accepting that the treatment itself is part of the problem.

Some experts, like Dr. Perry Fine, argue OIH is overdiagnosed. He points out that many human studies use experimental pain (like heat on the skin), not real-world chronic pain. But clinical evidence-patient reports, dose-response patterns, and response to tapering-supports its existence in real patients.

The FDA now requires opioid labels to mention OIH as a possible side effect. Pain fellowships are teaching it. But awareness still lags behind evidence.

What’s Next for OIH?

Research is moving fast. The NIH is funding a study (NCT05217891) looking for genetic markers that predict who’s most likely to develop OIH. Two commercial genetic tests are expected to launch in early 2025, helping doctors choose safer pain meds from the start.

Pharmaceutical companies are also developing new drugs that block NMDA receptors without ketamine’s side effects. Three are in late-stage trials. The goal? Treat OIH without removing opioid relief entirely.

Meanwhile, opioid prescriptions in the U.S. have dropped 44% since 2016. But over 10 million Americans still take long-term opioids. For them, recognizing OIH isn’t optional-it’s essential.

What Should You Do If You Suspect OIH?

If you’re on opioids and your pain is getting worse despite higher doses:

- Track your pain: Note when it started, where it is, what makes it better or worse.

- Don’t increase your dose on your own.

- Ask your doctor: "Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?"

- Request a pain specialist referral if your doctor isn’t familiar with OIH.

- Be prepared to taper slowly. Improvement takes time, but it’s possible.

You’re not weak. You’re not "addicted." You’re experiencing a known biological response to medication. And it can be fixed.

Is opioid-induced hyperalgesia the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive drug use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physical change in pain processing. You can have OIH without addiction, and addiction without OIH. The treatments are different: addiction needs behavioral support and sometimes medication-assisted therapy; OIH needs dose reduction and targeted pain modulation.

Can I stop opioids cold turkey if I have OIH?

No. Stopping abruptly can cause severe withdrawal and make your pain worse. OIH responds best to gradual tapering-usually 10-25% every few days. Sudden stops can trigger rebound pain, anxiety, and even hospitalization. Always work with your doctor on a safe plan.

Does everyone who takes opioids get OIH?

No. Only about 2-15% of long-term users develop it. Risk goes up with higher doses, longer use, kidney issues, and certain genetic factors. Most people on low-to-moderate doses for short periods don’t develop OIH. But if your pain worsens with higher doses, it’s worth checking.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people notice improvement in 2-4 weeks after starting a taper. Full recovery of normal pain sensitivity can take 4-8 weeks. Some patients need longer, especially if OIH was severe or untreated for months. Patience and consistency are key.

Are there any new treatments for OIH on the horizon?

Yes. Three new drugs targeting NMDA receptors are in late-stage clinical trials as of 2024. Genetic tests to identify high-risk patients are expected in early 2025. These could help doctors choose safer pain meds from the start and prevent OIH before it starts.

so like... you're telling me taking more painkillers makes your pain worse? wow. revolutionary. next you'll tell me drinking salt water won't cure dehydration. 🙄

In many traditional systems, pain is not merely a signal but a teacher. The body speaks through discomfort, and pharmaceutical suppression often silences the message before we hear it. OIH may be the nervous system’s last cry before surrender. We must listen, not just medicate.

I’ve seen this happen to my mom. She was on oxycodone for years after her surgery, and then suddenly even hugs hurt. Her doctor dismissed it as ‘anxiety’ until she pushed back. Tapering her dose changed everything. It’s not weakness-it’s biology. Thank you for writing this.

It is a well-documented phenomenon in neuropharmacology. The upregulation of NMDA receptors and subsequent central sensitization is not speculative. The literature dates back to the 1970s. The fact that this remains underrecognized speaks to systemic failures in medical education rather than scientific uncertainty.