Metformin and Liver Disease: How to Prevent Lactic Acidosis

Metformin is the most common pill prescribed for type 2 diabetes. Millions of people take it every day because it works, it’s cheap, and it’s been around for decades. But if you have liver disease, your doctor might tell you to stop taking it. Why? Because of something called lactic acidosis.

What Is Lactic Acidosis, Really?

Lactic acidosis isn’t a common side effect. It’s rare-about 3 to 10 cases per 100,000 people taking metformin each year. But when it happens, it’s serious. Your blood becomes too acidic because too much lactic acid builds up. That’s dangerous. Your organs start to shut down. You might feel nauseous, vomit, have stomach pain, or get dizzy. In severe cases, you’ll need to be put on a breathing machine.Metformin doesn’t cause lactic acidosis by itself. It’s the combination with a failing liver that’s the problem. Your liver normally clears lactic acid from your blood. If your liver is damaged, that job slows down. Metformin makes your body produce a little more lactic acid and blocks your liver from clearing it. When both things happen at once, lactic acid piles up.

Why Was Metformin Banned in Liver Disease?

Back in the late 1990s, doctors got scared. The old diabetes drug phenformin had caused hundreds of deaths from lactic acidosis. When metformin came along, they assumed the same risk. So guidelines said: no metformin if you have liver disease. Full stop.But here’s the twist: phenformin was metabolized by the liver. Metformin isn’t. It’s cleared by the kidneys. That’s a big difference. Studies since then have shown metformin is far safer. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study followed over 5,000 patients for 10 years. Zero cases of lactic acidosis. The COSMIC trial, which tracked nearly 9,000 people, also found no cases.

So why is the warning still there? Because the data on liver disease is still thin. Most of the warnings come from case reports-single patients who got sick. Not large studies. And many of those patients had other risk factors: alcohol use, kidney problems, or infections. That makes it hard to say if metformin was the real cause.

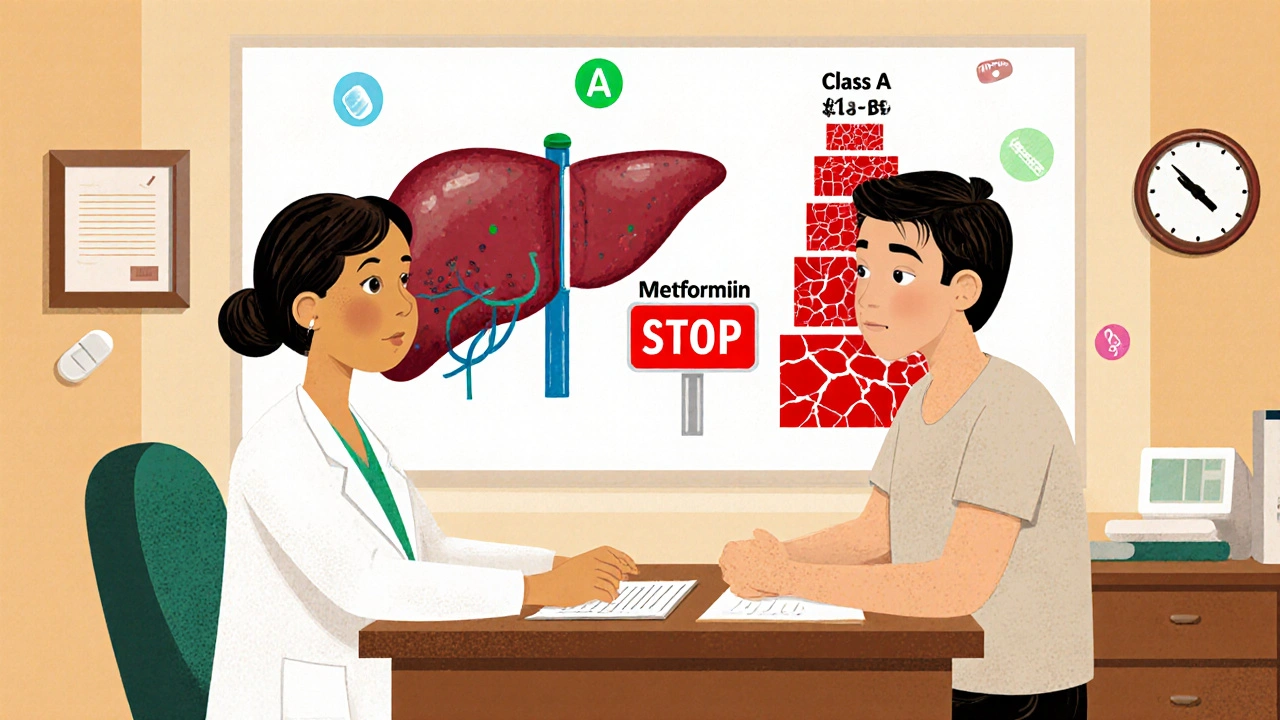

Not All Liver Disease Is the Same

This is where things get messy. You can’t treat all liver disease the same way.People with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-the most common type-are often overweight and have type 2 diabetes. Metformin helps both. It lowers blood sugar. It also reduces liver fat. Some studies show it can even improve liver inflammation. That’s why many doctors now quietly prescribe it to these patients.

But if you have cirrhosis, it’s a different story. Cirrhosis means your liver is scarred and can’t function well. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) says metformin might be okay if your cirrhosis is mild (Child-Pugh Class A). But if it’s moderate to severe (Class B or C), the risk jumps. Your liver can’t clear lactate. Your kidneys might be struggling too. That’s when lactic acidosis becomes a real threat.

A 2022 study of Veterans Affairs patients found only 8% of those with moderate cirrhosis were on metformin. That’s not because doctors are being overly cautious-it’s because the data says the risk isn’t worth it in those cases.

What Does the Latest Research Say?

In 2024, a case report in Cureus pointed out something surprising: there’s almost no solid evidence supporting the ban on metformin in mild liver disease. The authors called it a "historical artifact"-a rule that stuck around long after the reason for it faded.Dr. John B. Buse, former president of the American Diabetes Association, said in 2023: "The evidence against metformin in non-cirrhotic liver disease is remarkably weak." He’s not alone. The European Association for the Study of the Liver is drafting new 2025 guidelines that may actually recommend metformin as a first-choice drug for people with NAFLD and diabetes.

Meanwhile, the MET-REVERSE trial, running through 2025, is looking specifically at people with mild liver impairment. Early results show lactic acidosis occurred in just 0.02% of patients-almost the same rate as in people with healthy livers. That’s not zero. But it’s low enough that many experts now think the benefits outweigh the risks for mild cases.

When Is Metformin Absolutely Unsafe?

Even if you’re otherwise healthy, metformin can be dangerous in certain situations. You should stop taking it if:- You’re having surgery or a procedure that requires fasting

- You’re getting contrast dye for a CT scan

- You’re dehydrated from vomiting, diarrhea, or fever

- Your kidneys aren’t working well (eGFR below 30)

- You have active alcohol use disorder

In these cases, your body can’t clear metformin properly. That’s when levels build up and lactic acid starts to rise. The rule is simple: stop metformin 48 hours before any procedure and don’t restart until you’re eating normally and hydrated again.

How Do Doctors Monitor for Risk?

If you have mild liver disease and your doctor says it’s okay to stay on metformin, they’ll watch you closely. That means:- Checking your liver enzymes every 3 months

- Testing your kidney function (creatinine and eGFR) every 6 months

- Asking you to report any new nausea, fatigue, or muscle pain

- Testing your blood lactate level if you feel unwell

If your lactate level goes above 5 mmol/L and your blood pH drops below 7.35, that’s lactic acidosis. Treatment is urgent: IV fluids, oxygen, and sometimes sodium bicarbonate to balance your blood pH. In severe cases, hemodialysis is needed. It clears metformin from your blood 5 times faster than your kidneys can.

What Are the Alternatives?

If metformin isn’t safe for you, there are other options. SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin help lower blood sugar and also reduce liver fat. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) are even better-they promote weight loss and improve liver health. Both have lower lactic acidosis risk than metformin.But they’re more expensive. And not everyone can use them. If you’re on Medicare or have limited insurance, metformin might still be your best option-even with liver disease-if your condition is stable.

The Bottom Line

Metformin isn’t automatically dangerous if you have liver disease. But you can’t ignore the risk either.If you have fatty liver and no cirrhosis, metformin may help your liver and your blood sugar. Talk to your doctor about monitoring, not avoiding.

If you have moderate to severe cirrhosis, don’t take metformin. The risk of lactic acidosis is real, and the consequences can be fatal. Switch to a safer alternative.

The old rule-"no metformin with liver disease"-is outdated. But the new rule isn’t "go ahead and take it." It’s "assess carefully, monitor closely, and choose wisely." Your liver and your diabetes care should be managed together, not separately.

What Should You Do Next?

If you’re on metformin and have liver disease:- Ask your doctor what stage your liver disease is (Child-Pugh Class A, B, or C)

- Get your eGFR and liver enzymes checked in the last 6 months

- Know your symptoms: nausea, vomiting, unusual tiredness, rapid breathing

- Don’t skip your lab tests

- Stop metformin before any surgery or imaging with contrast dye

Don’t stop metformin on your own. But don’t ignore the warning signs either. The goal isn’t to avoid all risk-it’s to manage it smartly.

Can I take metformin if I have fatty liver disease?

Yes, if your fatty liver disease is mild and you don’t have cirrhosis, metformin is often safe and may even help reduce liver fat. Many doctors now prescribe it for this reason. But you need regular monitoring of liver enzymes and kidney function. Always follow up with your provider.

Is metformin safe with cirrhosis?

It depends on how advanced the cirrhosis is. For mild cirrhosis (Child-Pugh Class A), metformin may be used with close monitoring. For moderate to severe cirrhosis (Class B or C), it’s not recommended. Your liver can’t clear lactic acid well, and the risk of lactic acidosis rises sharply. Always get your liver function graded before starting or continuing metformin.

What are the warning signs of lactic acidosis from metformin?

Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, unusual tiredness, muscle aches, trouble breathing, dizziness, and a slow or irregular heartbeat. If you feel suddenly weak or short of breath, stop taking metformin and seek medical help right away. These symptoms can develop quickly and become life-threatening.

Should I stop metformin before a CT scan?

Yes. Always stop metformin at least 48 hours before any procedure involving contrast dye. The dye can temporarily reduce kidney function, which increases metformin buildup. Restart only after your kidney function is confirmed normal and you’re eating and drinking normally again.

Are there better diabetes drugs than metformin for liver disease patients?

Yes. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin) and GLP-1 agonists (like semaglutide) are safer for people with liver disease and can even improve liver health. They’re more expensive, but if metformin is risky for you, they’re often the next best choice. Talk to your doctor about switching if you have moderate liver damage.

How often should I get blood tests if I’m on metformin with liver disease?

Every 3 months for liver enzymes (ALT, AST) and kidney function (creatinine, eGFR). If you have mild liver disease and are stable, you might stretch this to every 6 months. But if your liver numbers change or you feel unwell, test sooner. Don’t wait for symptoms to appear.

Does alcohol make metformin more dangerous for the liver?

Yes. Alcohol stresses the liver and increases lactic acid production. If you drink regularly, especially heavily, metformin becomes much riskier. Many doctors will refuse to prescribe it if you have active alcohol use disorder. If you’re trying to cut back, talk to your doctor-you may need to switch medications until your liver recovers.

Finally, someone lays it out without the fear-mongering. I’ve been on metformin for 12 years with NAFLD, and my liver enzymes have improved. My doc started me on it because I was prediabetic, and now my HbA1c is 5.2. The old warnings are relics from a time when we didn’t have good data. It’s time to stop treating patients like they’re walking time bombs.

Oh wow, so now we’re just gonna ignore decades of medical caution because some ‘studies’ say it’s fine? Next you’ll tell me it’s safe to take insulin with cirrhosis too. Real responsible.

The real tragedy isn’t metformin-it’s the institutional inertia that refuses to update guidelines based on evidence. The ban was born from phenformin’s corpse, and now it haunts patients like a ghost in the machine. We treat diabetes with algorithms, yet our protocols are stuck in 1998. That’s not medicine. That’s liturgy.

So… we’re just supposed to trust this now? Cool. I’ll just keep my meds and ignore my liver until I pass out. 🤷♀️

Every time someone says 'the data is thin,' it means 'I don't like the evidence.' This isn't science-it's wishful thinking dressed up in jargon. People die from lactic acidosis. You think your anecdote trumps a black box warning? Wake up.

I’ve seen patients with mild cirrhosis stay on metformin for years with no issues-so long as they’re monitored. It’s not about black-and-white rules. It’s about individual risk. If your liver’s barely affected and your kidneys are fine, why deny someone a cheap, effective drug? Let’s stop treating patients like statistics.

OMG I JUST GOT DIAGNOSED WITH NAFLD AND I’M ON METFORMIN AND NOW I’M SCARED BUT ALSO HOPEFUL?? MY DOCTOR SAID IT’S FINE BUT I’M STILL PANICKING 😭 I JUST WANT TO LIVE AND NOT BE A STATISTIC PLEASE HELP

While the evidence supporting metformin use in mild liver disease continues to grow, clinical decision-making must remain individualized. Regular monitoring of renal function, liver enzymes, and lactate levels remains essential. For patients with Child-Pugh Class A cirrhosis, the benefit-risk profile may favor continuation, provided no other contraindications exist. Always consult with your care team before making changes.

So now we’re letting Big Pharma rewrite medical guidelines? Next they’ll say aspirin’s fine for pregnant women. This is why America’s healthcare is a joke. Follow the damn warning. Your liver doesn’t care about your ‘studies.’

Ohhhhh so you're telling me I've been taking metformin for 7 years with fatty liver and I'm not dying?? But my cousin's neighbor's uncle died from it in 2010 and now you're saying it's safe?? I'm so confused... also my mom says you should never take anything that's not 'natural' so I'm gonna stop now. 💅

Just had my 6-month labs-eGFR 78, ALT 38, lactate normal. Still on metformin. My NAFLD is improving. 🙌 Doc says keep going. If you’re stable, don’t panic. If you’re scared, ask for a second opinion. You got this. 💪

It is, without question, a matter of profound intellectual disarray that the medical community continues to cling to archaic contraindications predicated upon obsolete pharmacokinetic assumptions. The data from the MET-REVERSE trial, coupled with the UKPDS and COSMIC studies, constitutes an overwhelming body of evidence that renders the current warnings anachronistic. One must, therefore, conclude that the persistence of these guidelines reflects not clinical prudence, but institutional cowardice.

lol so metformin's fine now? i bet you also think smoking is 'maybe okay if you do it in moderation' and your liver is just 'kinda lazy'. my uncle died from this. you're not a doctor. stop giving advice. 🤡

And yet, here we are. My doctor’s updated his protocol after reading the 2024 Cureus paper. He’s now prescribing metformin to 80% of his NAFLD patients. Guess what? No ER visits. No lactic acidosis. Just better HbA1c and less belly fat. Maybe the real danger isn’t the drug-it’s the fear.