Medications for Treating Polyposis: Benefits, Options & Tips

Polyposis Medication Selector

This tool helps you understand which medications might be most appropriate for your specific polyposis situation based on your genetic subtype, polyp burden, age, and health conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Medications can shrink or prevent polyps in many polyposis syndromes, especially when surgery isn’t feasible.

- NSAIDs (e.g., aspirin, sulindac) and COX‑2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) have the strongest evidence for chemoprevention.

- Genetic subtype (FAP vs. SPS) and patient age drive drug choice and dosing.

- Regular monitoring-colonoscopy, blood tests, and side‑effect checks-is essential for safe long‑term use.

- Combine medication with lifestyle tweaks (diet, smoking cessation) for the best risk‑reduction plan.

What Exactly Is Polyposis?

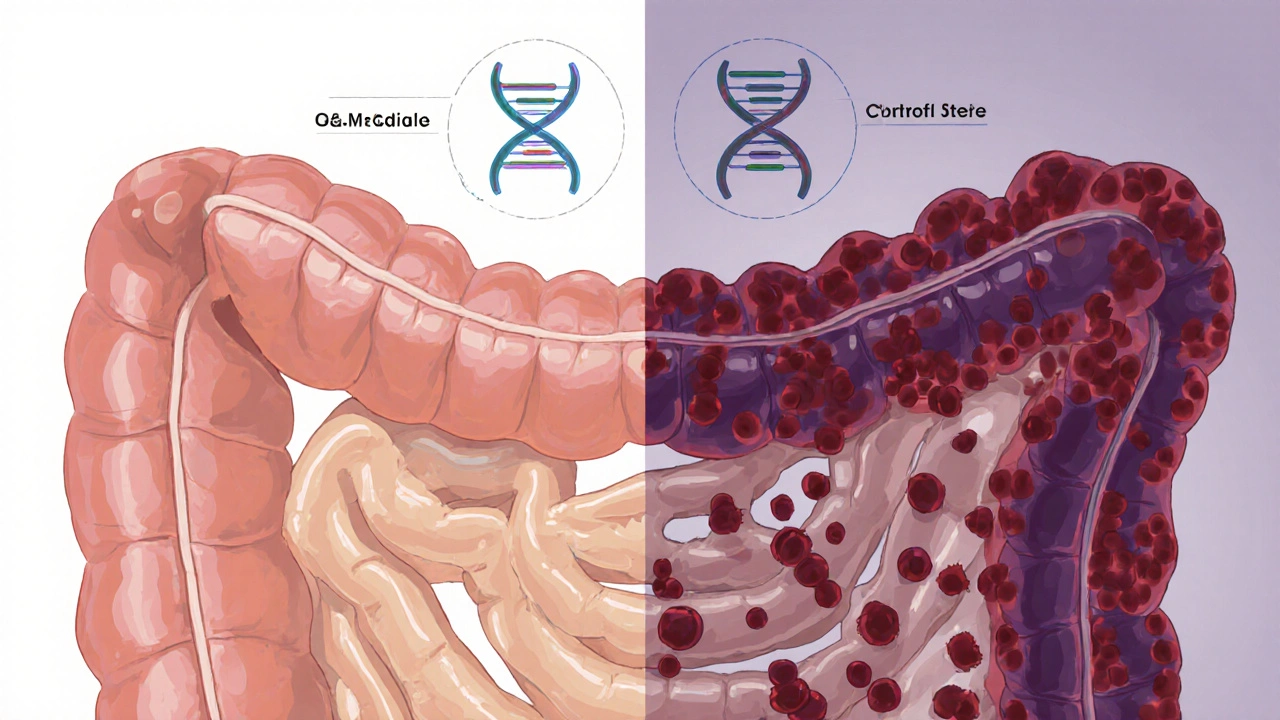

Polyposis is a group of disorders where dozens to thousands of polyps develop in the colon or other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. The condition usually stems from inherited gene mutations, the most common being the APC gene linked to familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Other forms, like Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS), follow different pathways but share the risk of turning benign growths into cancer.

Polyps themselves vary: adenomatous (pre‑cancerous), hyperplastic (usually low risk), and sessile serrated lesions (higher malignant potential). Knowing the type guides both surveillance intervals and medication strategies.

Why Medications Matter in Polyposis Management

Most people think the only answer is surgical removal-colectomy for FAP, for example. While surgery remains curative in many cases, drugs offer a less invasive, cost‑effective way to keep polyp numbers low, delay surgery, or manage residual disease after surgery.

Enter polyposis medication. These agents work by targeting inflammation, cell‑growth pathways, or the genetic triggers that feed polyp formation. The goal isn’t just symptom relief; it’s true chemoprevention-reducing the chance that a small polyp ever becomes cancer.

Drug Classes with Real‑World Evidence

Below are the most studied medication families for polyposis, along with typical doses, efficacy numbers, and common side‑effects. All data reflect studies published up to 2024.

| Medication | Typical Dose | Polyp Reduction (average) | Key Side‑effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 81-325mg daily | ≈30% fewer adenomas over 2years | GI irritation, bleeding risk |

| Sulindac | 150mg twice daily | ≈45% reduction in polyp size | Headache, rash, renal effects |

| Celecoxib | 200mg twice daily | ≈40% fewer new polyps | Cardiovascular risk, hypertension |

| Erlotinib (EGFR inhibitor) | 150mg daily | ≈25% shrinkage in refractory polyps | Rash, diarrhea, fatigue |

| Sirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) | 2mg daily | ≈20% reduction in polyp count | Infection risk, hyperlipidemia |

Non‑steroidal Anti‑inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs act on cyclo‑oxygenase (COX) enzymes, cutting down prostaglandin‑driven inflammation that fuels polyp growth. Early trials with sulindac showed dramatic shrinkage of duodenal adenomas in FAP patients, prompting larger studies that confirmed a 45% average size reduction.

However, long‑term NSAID use can stress the stomach lining and kidneys. For patients with a history of ulcers or renal insufficiency, low‑dose aspirin-a milder NSAID-might be safer, though its protective effect is modest.

COX‑2‑Selective Inhibitors

Celecoxib blocks the COX‑2 isoform responsible for inflammation while sparing COX‑1, which protects the stomach. A 2022 multicenter trial in FAP showed a 40% decline in new polyp formation over three years, with fewer GI side‑effects than non‑selective NSAIDs.

The trade‑off is a slightly higher cardiovascular risk, especially in patients over 60 or with existing heart disease. In those cases, doctors may combine a low‑dose aspirin with a statin to mitigate the threat.

Aspirin - The Old‑School Hero

Low‑dose Aspirin has been studied in multiple colorectal‑cancer‑prevention trials. For polyposis, a randomized 2021 study of 81mg daily showed a 30% drop in adenoma number after two years, with the added benefit of cardiovascular protection.

Bleeding remains the biggest concern, so clinicians often run baseline hemoglobin checks and advise patients to avoid concurrent NSAIDs.

Targeted Therapies: EGFR & mTOR Inhibitors

When polyps become resistant to NSAIDs, oncologists sometimes turn to EGFR inhibitors like erlotinib. These drugs block the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway, a driver in many colorectal cancers. Small pilot studies suggest a 25% shrinkage in refractory polyps, but skin rash and diarrhea limit long‑term use.

mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus target cellular growth signals downstream of APC mutations. Early‑phase data show a 20% reduction in polyp count, yet immunosuppression risk means they’re reserved for severe cases where surgery is high risk.

Choosing the Right Medication for You

There isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all pill. The best choice hinges on four practical factors:

- Genetic subtype: FAP patients (APC mutation) respond best to NSAIDs or COX‑2 inhibitors. SPS patients, who often have a BRAF‑driven pathway, may need a combination of aspirin and lifestyle changes.

- Polyp burden: If you have fewer than 50 adenomas, low‑dose aspirin might suffice. Over 100 polyps usually requires a stronger NSAID or a COX‑2 inhibitor.

- Age and comorbidities: Young adults (under 30) tolerate NSAIDs well; older adults need cardiovascular risk assessment before celecoxib.

- Side‑effect tolerance: History of ulcers pushes clinicians toward COX‑2 selective drugs, while a heart condition nudges them toward aspirin plus a statin.

Discuss these points with your gastroenterologist; they’ll tailor a regimen and set up a monitoring schedule.

Practical Management Tips

- Baseline labs: Check CBC, liver enzymes, and renal function before starting any NSAID or targeted therapy.

- Start low, go slow: Begin with the lowest effective dose. For aspirin, 81mg daily is often enough; increase only if polyp counts stay high after 12months.

- Scheduled colonoscopies: Even on medication, surveillance every 1-2years is essential. Your endoscopist will note any change in polyp size or number.

- Watch for red flags: New GI pain, unexplained bruising, or persistent diarrhea should trigger an urgent review.

- Combine with lifestyle: High‑fiber diet, limited red meat, and regular exercise boost the drug’s preventive effect.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I prevent polyps without medication?

Lifestyle changes-high fiber, low processed meat, quitting smoking-lower the risk but rarely replace medication for high‑risk genetic syndromes. Most guidelines still recommend a chemopreventive drug alongside surveillance.

How long should I stay on a polyposis medication?

Typically indefinitely, as long as the drug remains effective and side‑effects are manageable. Some patients stop after colectomy because the colon is gone, but they may need continued therapy for residual duodenal polyps.

Are there any natural supplements that work like NSAIDs?

Curcumin and omega‑3 fatty acids show modest anti‑inflammatory effects, but current evidence doesn’t match the potency of prescription NSAIDs. They can be added as adjuncts, not replacements.

What if I develop an ulcer while taking NSAIDs?

Stop the NSAID immediately and start a proton‑pump inhibitor (PPI). Your doctor may switch you to a COX‑2‑selective drug or low‑dose aspirin combined with a PPI.

Is chemoprevention covered by insurance?

In Canada, most provincial plans cover aspirin and generic NSAIDs when prescribed for a documented condition like polyposis. Specialized drugs such as celecoxib or targeted agents often require prior authorization.

Bottom line: medications are a powerful part of the polyposis playbook. By matching the drug to your genetic profile, polyp load, and health status, you can keep the colon healthier for years-sometimes even avoiding major surgery. Talk to your gastroenterology team, set up a monitoring calendar, and stay proactive. Your future self will thank you.

Aspirin’s low‑dose regimen is a solid starting point for younger patients with a modest polyp count. It also offers the bonus of cardiovascular protection when tolerated.

From a chemopreventive standpoint, the pharmacodynamics of COX‑2 selective inhibitors like celecoxib provide a favorable risk‑benefit ratio in FAP cohorts, assuming vigilant cardiovascular monitoring. Meanwhile, sulindac’s dual COX inhibition profile yields robust adenoma regression but mandates renal surveillance. The integration of these agents into a genotype‑guided algorithm underscores precision medicine in hereditary polyposis.

Let’s unpack the therapeutic landscape for polyposis with some nuance. First, the historical reliance on non‑selective NSAIDs laid the groundwork for modern chemoprevention, yet their gastrointestinal toxicity remains a limiting factor. Aspirin, at 81 mg daily, has demonstrated roughly a 30 % reduction in adenoma burden over two years, but this benefit is modest when juxtaposed against higher‑dose sulindac, which can shave nearly half of polyp size in a comparable timeframe. However, sulindac’s renal implications cannot be ignored, particularly in patients with pre‑existing nephropathy. COX‑2 inhibitors like celecoxib have carved a niche by sparing the gastric mucosa, but they shift the risk vector toward cardiovascular events, necessitating a comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment before initiation. In patients over 60 or those with established heart disease, the addition of low‑dose aspirin or even a statin may mitigate some of this risk, but the decision matrix remains complex. Targeted agents such as erlotinib and sirolimus represent the frontier for refractory cases, offering a mechanistic approach by inhibiting EGFR and mTOR pathways respectively. Their efficacy, hovering around a 20‑25 % reduction in polyp burden, is tempered by side‑effects like rash, diarrhea, and immunosuppression, which often limit long‑term adherence. Age stratification is also pivotal; younger patients (<30) typically tolerate NSAIDs well, whereas older cohorts benefit more from COX‑2 selectivity if cardiovascular risk is low. Additionally, comorbidities such as ulcer disease push clinicians toward COX‑2 inhibitors or aspirin paired with a proton‑pump inhibitor for gastric protection. Regular surveillance colonoscopies every 1‑2 years remain the cornerstone of management, catching any uptick in polyp number or size before malignant transformation. Lifestyle adjuncts-high‑fiber diets, reduced red meat intake, and regular exercise-can synergize with pharmacotherapy, enhancing overall chemopreventive efficacy. Ultimately, a personalized plan anchored in genetic subtype, polyp burden, age, and comorbid landscape offers the best chance to defer or avoid surgical interventions while minimizing drug‑related toxicity.

Low‑dose aspirin is often the go‑to for those just starting out on chemoprevention, especially if they have a clean GI slate.

Those on sulindac should definitely keep an eye on their kidney function; a quarterly creatinine check can catch problems early.

Don't forget to pair any NSAID with a PPI if you have a history of ulcers 😊👍

Hang in there! Even a small drop in polyp count can make a huge difference over time.

While the long‑form analysis is thorough, remember that real‑world adherence often drops when patients experience even mild side‑effects. Practical strategies-like rotating NSAIDs, using enteric‑coated formulations, or timing doses with meals-can improve tolerance. Moreover, genetic counseling should accompany any medication plan to ensure patients understand the hereditary nature of their condition and the importance of family screening.

If you’re over 100 polyps, stop messing around with aspirin alone and jump to a COX‑2 inhibitor or combination therapy now.

Just a heads‑up: whatever you choose, keep a log of symptoms and lab results. It helps your doctor fine‑tune the dose later.

Don’t chase every new drug hype.

Think of chemoprevention like seasoning a soup – a pinch of aspirin, a dash of celecoxib, and a sprinkle of lifestyle tweaks can turn a bland routine into a flavorful, cancer‑fighting feast!