Liability and Indemnification in Generic Transactions: What You Need to Know

When you sign a contract-whether you're buying software, hiring a contractor, or selling a business-you're not just agreeing to deliver a product or service. You're also agreeing to take on risk. And that’s where liability and indemnification come in. These aren’t just legal buzzwords. They’re the backbone of how businesses protect themselves when things go wrong.

Imagine this: You buy a piece of medical equipment from a vendor. Six months later, it fails and causes harm to a patient. The hospital gets sued. Now, who pays? The hospital? The vendor? Or someone else? Without a clear indemnification clause, you’re stuck in court, guessing who’s on the hook. But with a well-drafted clause, you know upfront: the vendor covers the legal fees, the settlement, even the cost of notifying affected patients. That’s not luck. That’s contract design.

What Indemnification Actually Means

Indemnification is a promise in a contract: one party agrees to pay for losses the other party suffers because of something specific. It’s not insurance, but it works like it. If a third party sues you because of the other side’s mistake, the indemnifying party steps in and covers the cost.

The legal definition is simple: to indemnify means to compensate someone for losses they’ve incurred. According to California case law (Crawford, 44 Cal. 4th 541), it’s about paying for legal liabilities-not just fixing the problem, but making the injured party whole again. That includes court costs, attorney fees, settlements, and even fines.

But here’s what most people miss: indemnification isn’t one thing. It’s three separate promises bundled together:

- Indemnify: Pay for the losses.

- Defend: Pay for lawyers and handle the lawsuit.

- Hold harmless: Don’t come after me if I’m sued because of your actions.

Many contracts say “indemnify, defend, and hold harmless” like it’s one phrase. But legally, they mean different things. If your contract only says “indemnify,” you might get reimbursed after the fact-but no one’s paying your lawyers while the case is ongoing. That can bankrupt you before you even win.

When Does Indemnification Kick In?

Not every mistake triggers it. The contract has to say exactly what does. These are called triggering events.

Common triggers include:

- Breach of warranty (e.g., the software doesn’t work as promised)

- Violation of law (e.g., the vendor used stolen patient data)

- Intellectual property infringement (e.g., the medical device uses a patented design without permission)

- Negligence (e.g., improper installation caused injury)

- Failure to disclose known risks (e.g., hiding a recall history)

Let’s say you’re a pharmacy buying a new inventory system. The vendor claims it’s HIPAA-compliant. Later, it’s found to have a security flaw that exposed patient records. That’s a triggering event. The vendor’s indemnification clause should cover the cost of notifying patients, credit monitoring, regulatory fines, and legal defense.

But if the contract says “indemnification only applies to third-party claims,” and the government fines you directly? You’re on your own. That’s why precision matters.

Who Pays? Mutual vs. One-Sided

Indemnification isn’t always one-way. There are two main types:

- Unilateral: Only one party pays. Common in vendor-customer deals. For example, a software company indemnifies its clients if its code violates someone’s patent.

- Mutual: Both parties protect each other. Often seen in joint ventures or construction contracts where both sides could cause harm.

Most generic transactions-like buying medical supplies or signing a lab services agreement-are unilateral. The vendor indemnifies the buyer. Why? Because the buyer usually has more leverage. A hospital won’t sign a contract unless the vendor agrees to cover liability from faulty equipment. But the vendor rarely agrees to indemnify the hospital for its own missteps, like mislabeling a drug.

That imbalance is normal. But it’s also where negotiations get heated. Sellers want to limit their exposure. Buyers want full protection. The middle ground? Caps, deductibles, and survival periods.

The Hidden Rules: Caps, Deductibles, and Survival Periods

Indemnification doesn’t mean unlimited liability. Smart contracts put limits on it.

Cap on liability: The maximum amount the indemnifying party will pay. In a $5 million equipment sale, the cap might be $1 million. That protects the vendor from being wiped out by one claim.

Deductible (or basket): The amount of loss that must occur before indemnification kicks in. If the basket is $50,000, the buyer absorbs the first $50K in losses. Only after that does the vendor pay. This stops small, routine claims from turning into legal battles.

Survival period: How long after the deal closes can you still make a claim? For basic warranties (like “we own this equipment”), survival might be 12 months. For critical ones-like tax liability or ownership of IP-it could be 3-5 years. Some jurisdictions even allow survival for fraud claims indefinitely.

These aren’t optional. They’re standard in M&A and commercial deals. If your contract doesn’t mention them, you’re leaving yourself exposed. A $200,000 claim could become a $2 million problem if there’s no cap.

What About Insurance?

What good is a promise to pay if the other party is broke? That’s why most contracts require the indemnifying party to carry insurance.

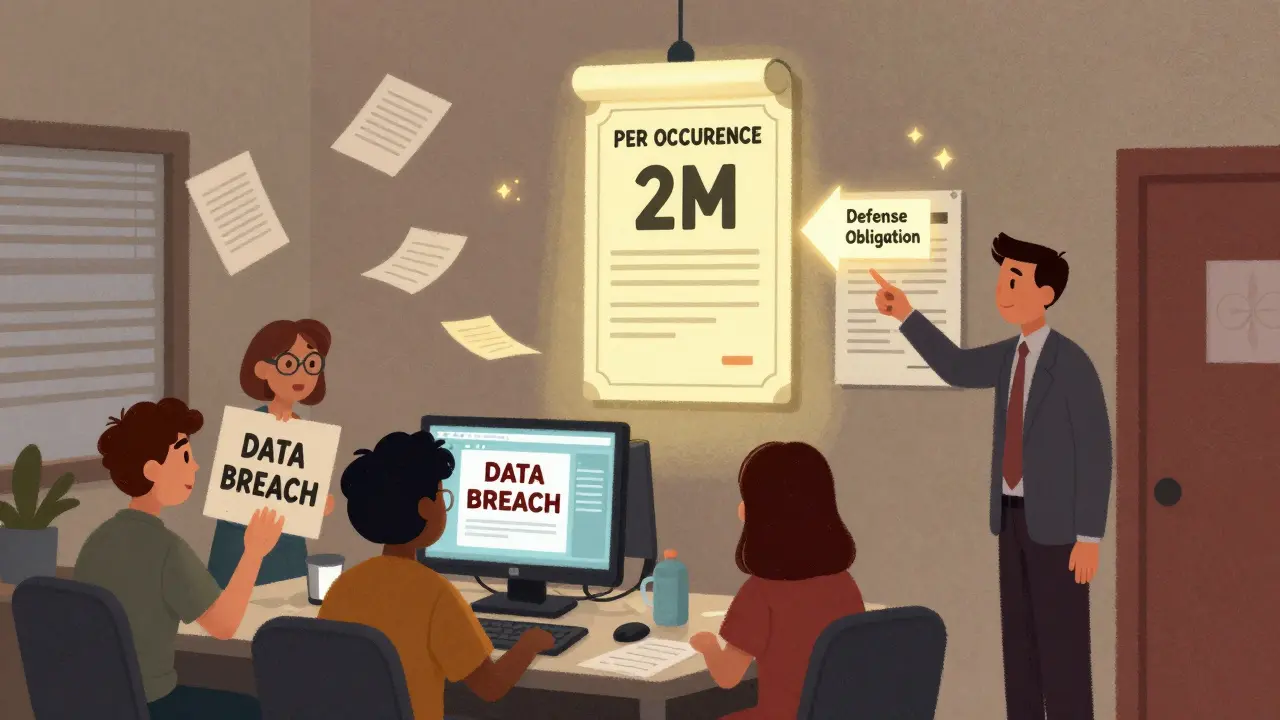

Look for language like: “Seller shall maintain general liability insurance of at least $2 million per occurrence and $5 million aggregate, naming Buyer as additional insured.”

Without this, you could win a legal battle and still get nothing. A vendor with no insurance and no assets? Indemnification is just words on paper. Always verify coverage. Ask for a certificate of insurance before signing.

How to Handle a Claim

Indemnification doesn’t work if you don’t follow the rules. Most contracts have strict procedures:

- Notify the indemnifying party immediately after learning of a claim.

- Provide all documents and details-no delays.

- Let them control the defense (if they’re paying).

- Don’t settle without their written approval.

Break any of these, and you could lose your right to indemnification. Courts have ruled against buyers who settled claims without telling the vendor. Why? Because the vendor might have had a better defense-or even a counterclaim.

And here’s a big one: if the contract says the indemnifying party “controls the defense,” you can’t pick your own lawyer. That’s intentional. The party paying wants to manage costs. But if you’re unhappy with their defense, most contracts let you hire your own lawyer at your own expense-and still get reimbursed later, if you win.

Why This Matters in Real Life

Think about a small clinic that signs a contract with a telehealth platform. The platform promises “HIPAA-compliant encryption.” But it’s not. A data breach happens. Patients sue. The clinic faces fines from Health Canada and lawsuits from patients.

If the contract has a strong indemnification clause, the platform pays for everything: legal fees, patient notifications, credit monitoring, even the cost of upgrading their system. The clinic survives.

If the clause is weak-“indemnify only for third-party claims, no defense obligation, no insurance required”-the clinic is on the hook for hundreds of thousands of dollars. And they didn’t even build the software.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, a Canadian pharmacy chain lost $1.8 million after a vendor’s billing system failed to comply with provincial drug pricing rules. The contract had no indemnification clause for regulatory violations. The vendor walked away. The clinic paid.

What to Do Before Signing

Don’t wait until something goes wrong. Before you sign any contract:

- Read the indemnification section. Don’t skip it.

- Check for caps, deductibles, and survival periods.

- Confirm insurance requirements are clear and enforceable.

- Ask: “Does this cover what I actually care about?”

- Get legal advice-even if it’s just a quick review.

And if you’re the seller? Don’t just say “yes” to everything. Push back. Limit the scope. Exclude indirect damages (like lost profits). Make sure the cap is reasonable. You’re not being unreasonable-you’re being smart.

Indemnification isn’t about trust. It’s about risk management. Even the best partners make mistakes. The contract isn’t there to punish them-it’s there to make sure you don’t pay for their errors.

What’s the difference between liability and indemnification?

Liability is the legal responsibility for harm or loss. Indemnification is a contractual promise to pay for that liability. You can be liable without indemnification-and vice versa. Indemnification turns potential liability into a predictable cost.

Can I waive indemnification entirely?

Yes, but it’s risky. Most businesses won’t sign without it, especially in healthcare, tech, or supply chain deals. If you’re the buyer, waiving it means you’re accepting full risk. If you’re the seller, you might lose the deal. It’s rarely a good idea unless you’re dealing with a trusted partner under a very low-risk transaction.

Does indemnification cover punitive damages?

Usually not. Most contracts exclude punitive damages because they’re meant to punish, not compensate. Courts in Canada and the U.S. often won’t enforce indemnification for punitive damages unless the contract explicitly says so. Always check the exclusions section.

What if the indemnifying party goes bankrupt?

Then you’re out of luck-unless they had insurance. That’s why insurance requirements are critical. If the contract requires insurance and the vendor didn’t get it, you may have grounds to sue for breach of contract. But recovering money from a bankrupt company is nearly impossible.

Do I need a lawyer to draft indemnification clauses?

You don’t have to, but you should. Boilerplate clauses often leave gaps. A lawyer can help you define triggering events, set realistic caps, and ensure insurance terms are enforceable. A poorly written clause can cost you more than the legal fee.

Final Thought

Liability is inevitable. Indemnification is optional-but it’s the difference between surviving a mistake and being crushed by it. In any transaction, whether it’s a $500 software license or a $5 million equipment deal, the party that understands indemnification wins. Not because they’re aggressive. But because they’re prepared.

Let me guess - you think indemnification is just a ‘legal buzzword’? Nah. This is how corporations weaponize contracts to shift every single risk onto the buyer while they walk away with the cash. You think a hospital has any real power here? Please. The vendor writes the clause, the hospital signs it because they’re desperate for equipment, and then when the device kills someone? The vendor’s lawyer laughs while the hospital files for bankruptcy. This isn’t risk management - it’s legalized predation.

While your analysis is technically accurate, it fundamentally misunderstands the structural imbalance inherent in modern commercial contracts. Indemnification clauses are not neutral risk-allocation tools - they are instruments of asymmetric power. The vendor’s cap on liability? A deliberate design to ensure that the cost of negligence remains externalized. The ‘insurance requirement’? Often unenforceable, as vendors shell out to offshore entities with zero assets. You cite Crawford v. California - but did you notice that the plaintiff still had to litigate for seven years before seeing a dime? Indemnification is theater. The real protection is in capital, not clauses.

Just wanted to add a real-world tip: if you're buying software or equipment, always ask for the vendor’s insurance certificate BEFORE signing. I’ve seen too many teams skip this because ‘it’s just a formality.’ Then a breach happens and they realize the vendor’s policy expired 3 months before the deal closed. Also - if the contract says ‘indemnify’ but not ‘defend,’ push back hard. Paying your own lawyers while waiting for reimbursement can kill a small business. A good clause should include: defense obligation, cap tied to contract value, survival period of at least 3 years, and named insured status. Don’t settle for less.

indemnify defend hold harmless - they say it like its one thing but its three different legal obligations. most people dont realize if you only get indemnify you might get paid back after 3 years of legal bills. but if you dont get defend you gotta pay your own lawyers while the vendor sits back. and if the cap is $100k on a $2m deal? good luck. also dont forget survival period. if its 12 months and a patent issue pops up at 14? youre screwed. always read the fine print. its not paranoia its practice.

They say ‘indemnification turns liability into a predictable cost’ - yeah, predictable for the corporation. For the small clinic? It’s a death sentence. The whole system is rigged. You think these vendors actually care about HIPAA? They sell to the highest bidder. The government doesn’t enforce. The courts are backlogged. And the buyer? They’re left holding the bag while the vendor moves on to the next state with a new LLC. This isn’t contract law - it’s corporate colonialism dressed up in legalese.

I just want to say thank you for writing this. I work in a small rural clinic and we signed a contract last year without reading the indemnification section. We got hit with a $300k fine because the billing software didn’t update for new state rules. The vendor said ‘sorry, not our problem.’ I cried for two days. Then I found this article. Now I read every contract like my life depends on it - because it does. You’re not just explaining law - you’re saving people.

Indemnification is just socialism for corporations. The rich get protected. The small guys pay.

It’s terrifying how many people treat contracts like they’re love letters. ‘Oh, they’re a nice vendor, they’d never screw us over.’ Honey. They’re not your friend. They’re a liability-averse machine with a legal team paid to bury you in clauses you didn’t read. I once watched a startup founder sign a $500k SaaS deal with no indemnification clause because ‘the CEO was really chill.’ Three months later, the software leaked 200k emails. The founder lost everything. The CEO? Bought a yacht. Indemnification isn’t about trust. It’s about survival.