Generic Drug Patents: How Exclusivity Periods Vary Across Countries

When a brand-name drug hits the market, it doesn’t stay alone for long. But how long it stays exclusive-before cheaper generics show up-depends entirely on where you live. In the U.S., Canada, the EU, or Japan, the rules are different. And those differences affect who gets access to affordable medicine, when, and why.

How Long Do Patents Last? It’s Not What You Think

Most people assume a drug patent lasts 20 years. That’s technically true-the patent clock starts ticking from the day the inventor files it, not when the drug is approved. But here’s the catch: drug development takes 10 to 15 years. By the time a pill gets approved by regulators, only 5 to 10 years of patent life are left. That’s not enough to recoup the average $2.3 billion spent on R&D per drug.

That’s why countries added extra layers. These aren’t patents. They’re called exclusivity periods. They don’t protect the invention. They protect the data used to prove the drug is safe and effective. No generic company can use that data to get approved until the exclusivity runs out-even if the patent expired years ago.

The U.S. System: A Maze of Rules

The U.S. has the most complex system. It layers five different types of exclusivity on top of patents:

- 5-year New Chemical Entity (NCE): No generic can even try to copy a brand-new drug for five years.

- 3-year exclusivity: For new uses, new formulations, or new delivery methods-like a pill that dissolves under the tongue instead of being swallowed.

- 7-year orphan drug exclusivity: For drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients). This one’s been a game-changer-12 new treatments for multiple myeloma were approved because of it.

- 6-month pediatric exclusivity: If a company tests a drug on kids, they get six more months of protection. It’s a reward, but also a strategy.

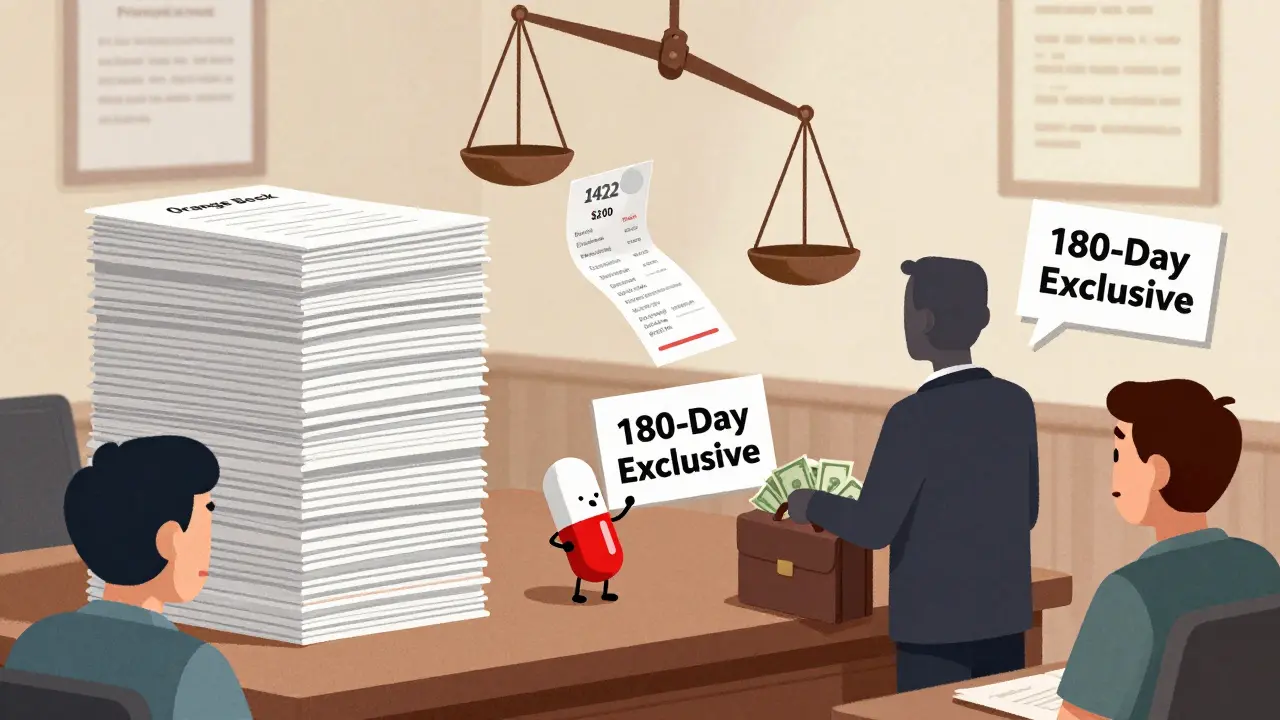

- 180-day generic exclusivity: This is the big one. The first generic company to challenge a patent and win gets a 180-day head start on the market. No one else can sell the same generic during that time. That’s worth hundreds of millions.

But here’s the dark side: companies pile on dozens of patents-sometimes over 100-for one drug. The average brand-name drug now has 142 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. This creates legal chaos. Generic makers have to fight through court cases just to get started. And sometimes, the brand company pays the generic maker to wait. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” deal. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these deals aren’t automatically illegal-but they’re still common. In 2023, 78% of U.S. pharmacists said they saw delays in generic availability because of these settlements.

Europe: The 8+2+1 Rule

The EU takes a cleaner, more predictable approach. Their system is called 8+2+1:

- 8 years of data exclusivity: Generic companies can’t use the brand’s clinical trial data to get approval.

- 2 years of market exclusivity: Even after those 8 years, the generic can’t be sold yet.

- 1-year extension: If the brand company adds a new, important use during the first 8 years, they get one more year.

So total protection? Usually 11 years. Sometimes 12. No 180-day bonus for the first challenger. No patent thicket games. That makes it easier for generics to enter-but also gives brand companies less room to stretch protection.

Canada follows the same model. So do Australia and New Zealand. But the EU’s system has a flip side: trade deals like CETA (Canada-EU trade agreement) force countries with cheaper generics to respect these data exclusivity rules-even after patents expire. That’s why HIV drugs stayed expensive in South Africa for over a decade after their patents expired.

Japan and China: Tighter Rules, Slower Access

Japan gives 8 years of data exclusivity and 4 years of market exclusivity. That’s 12 years total. China changed its rules in 2020, jumping from 6 to 12 years of data protection. Brazil followed in 2021 with 10 years. These moves were meant to attract drugmakers-but they’ve slowed down access to affordable medicines in middle-income countries.

In places like India and Thailand, where generics are a lifeline, regulators still let companies skip data exclusivity if the patent has expired. That’s why India makes 60% of the world’s generic drugs. But global trade pressure is pushing those countries to tighten rules too.

Why This Matters: Billions at Stake

Between 2023 and 2028, $356 billion in global brand drug sales will face generic competition. In the U.S., when a generic enters, the brand’s sales drop 80-90% within a year. That’s why companies fight so hard to delay generics.

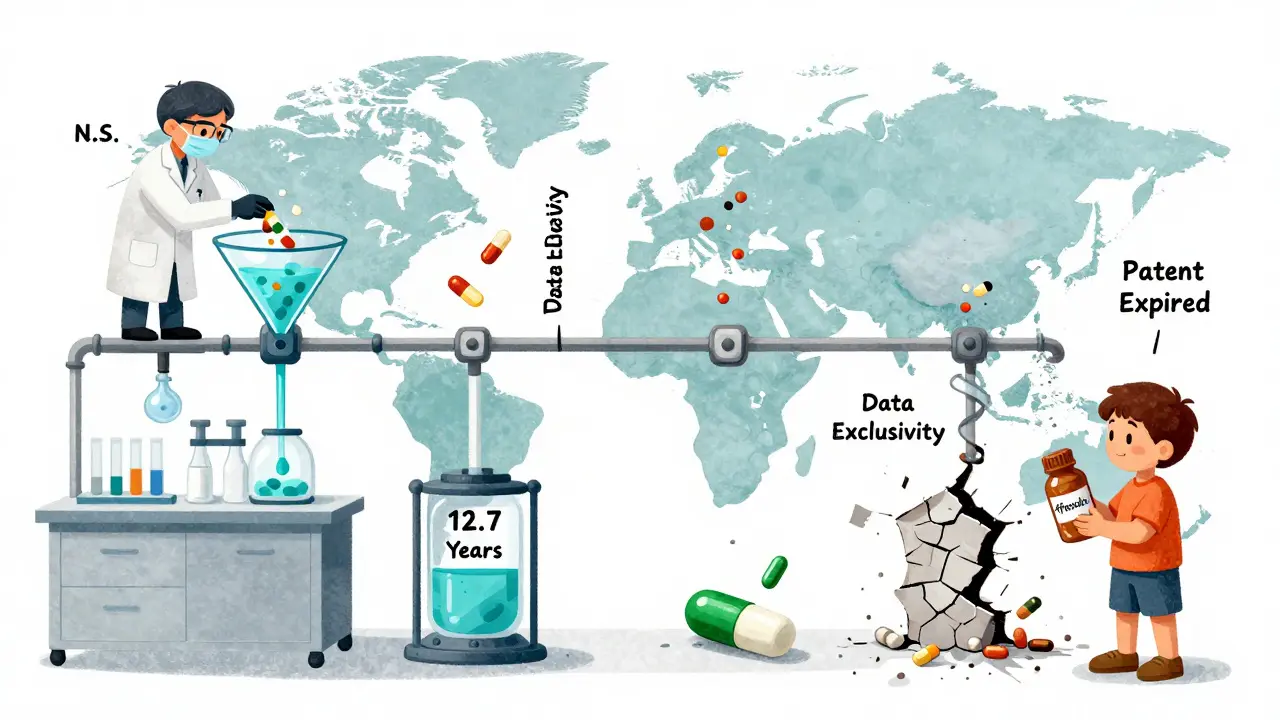

Take Keytruda, Merck’s cancer drug. Its effective market protection stretched from 8.2 years to 12.7 years thanks to patent extensions and exclusivity tricks. That’s not unusual. A 2022 study found that big pharma companies get an average of 38 extra patents per drug-not for new science, but for tiny changes: a new coating, a different dosage form, a new packaging.

Meanwhile, patients wait. The World Health Organization found that in low-income countries, generics arrive 19.3 years after a drug’s first approval. In high-income countries? Just 12.7 years. That’s a 6.6-year gap in access. And it’s not because of patents alone. It’s because of data exclusivity rules that block generics even after patents expire.

What’s Changing? The Fight Isn’t Over

There’s pressure to fix this. In the U.S., lawmakers are pushing the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act to ban pay-for-delay deals. The EU is considering cutting data exclusivity from 8 to 5 years for some drugs. Japan plans to speed up its patent review process. But big pharma isn’t backing down. PhRMA says without these protections, innovation would collapse.

Here’s the truth: innovation needs protection. But so does access. Right now, the system favors companies that game the rules over patients who need affordable drugs. The question isn’t whether exclusivity should exist. It’s whether it should last longer than the actual science behind the drug.

What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

By 2027, patent extensions and exclusivity periods will make up 45% of total market protection-up from 32% in 2020. That means even more delays. More legal battles. More money spent on lawyers instead of research.

Generic manufacturers are adapting. Some now spend $2-5 million just to build a legal strategy before they even make a pill. Others focus on drugs with weaker patent protection. A few, like Mylan with EpiPen, challenge 6 out of 12 patents-and redesign the product just enough to avoid infringement.

But for most patients, the system still feels rigged. A drug approved in 2015 might not have a generic until 2026. And that’s not because it’s too hard to copy. It’s because the rules were written to protect profits-not people.

How long does patent protection last for generic drugs in the U.S.?

The original patent lasts 20 years from the filing date, but because drug development takes so long, only 6-10 years remain after approval. Additional exclusivity periods-like 5-year NCE protection or 180-day generic exclusivity-can extend market control beyond the patent. In practice, many drugs have 12-15 years of exclusive sales before generics enter.

What is data exclusivity, and how is it different from a patent?

A patent protects the chemical formula or invention. Data exclusivity protects the clinical trial data submitted to regulators. Even if a patent expires, a generic can’t use the brand’s data to prove safety and effectiveness until data exclusivity runs out. In the U.S., data exclusivity lasts 5 years for new drugs; in the EU, it’s 8 years. This is often the biggest barrier to generic entry.

Why do some countries delay generic drugs even after patents expire?

Because of data exclusivity rules in trade agreements. For example, the EU’s 8-year data protection rule is enforced in countries like South Africa through trade deals. Even if a patent expires, generic makers can’t legally use the original data to get approval. That delays access by years-sometimes over a decade.

What is the 180-day exclusivity period in the U.S.?

It’s a reward for the first generic company to successfully challenge a brand-name patent through a Paragraph IV certification. That company gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic, with no competition. This incentive drives most generic challenges-but it’s also exploited through pay-for-delay deals, where brand companies pay generics to wait.

Can a generic drug enter the market before the patent expires?

Yes, but only if the generic company challenges the patent and proves it’s invalid or not infringed. In the U.S., this triggers the 180-day exclusivity. In the EU, generics can’t enter until exclusivity ends-even if the patent is weak. Courts in the U.S. often rule on these challenges, while the EU relies on regulatory timelines.

Do all countries have the same exclusivity rules?

No. The U.S. uses multiple overlapping exclusivities (5, 7, 3, 6-month, 180-day). The EU uses 8+2+1. Japan gives 8 years data + 4 years market. Canada matches the EU. Low-income countries often have no data exclusivity, allowing faster generic entry. Trade deals are pushing more countries toward stricter rules, even if it hurts access.