Cmax and AUC in Bioequivalence: What Peak Concentration and Total Exposure Really Mean

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it will? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab jargon-they’re the backbone of every generic drug approval worldwide. If these two values match closely between the original drug and its copy, the generic is considered safe and effective. No clinical trials needed. Just blood samples, math, and decades of science.

What Cmax Tells You About How Fast a Drug Hits

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It’s the highest level of drug found in your bloodstream after you take a dose. Think of it like the peak of a wave-how high does the drug rise before it starts to fade?

This number matters because some drugs only work when they hit a certain high point. Painkillers like ibuprofen need a sharp spike to block pain signals fast. If the generic version doesn’t reach a similar Cmax, you might feel the pain longer. On the flip side, drugs with narrow safety margins-like blood thinners or epilepsy meds-can turn dangerous if Cmax is too high. Too much warfarin? Risk of internal bleeding. Too little levothyroxine? Your metabolism slows down.

Regulators don’t just look at the number. They also check when it happens: Tmax, or time to reach Cmax. If the brand drug peaks at 2.5 hours and the generic peaks at 4 hours, that’s a red flag. Even if the peak height is close, the timing affects how you feel. A slower rise might mean delayed relief-or worse, uneven control of symptoms.

What AUC Reveals About Total Drug Exposure

AUC means area under the curve. It’s the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine drawing a graph of drug concentration in your blood from the moment you swallow the pill until it’s completely gone. AUC is the space under that curve.

This metric tells you how much of the drug your body actually absorbed. For antibiotics, antidepressants, or statins, total exposure matters more than speed. If your body doesn’t get enough of the drug over 24 hours, the infection might not clear, or your cholesterol won’t drop. AUC is the real measure of whether the drug did its job over time.

Unlike Cmax, which is a single snapshot, AUC is built from dozens of blood samples taken over hours or even days. The more data points, the more accurate the curve. Missing a sample during the early absorption phase? That can make AUC look lower than it really is. That’s why bioequivalence studies collect blood every 15 to 60 minutes at first, then less often as the drug clears.

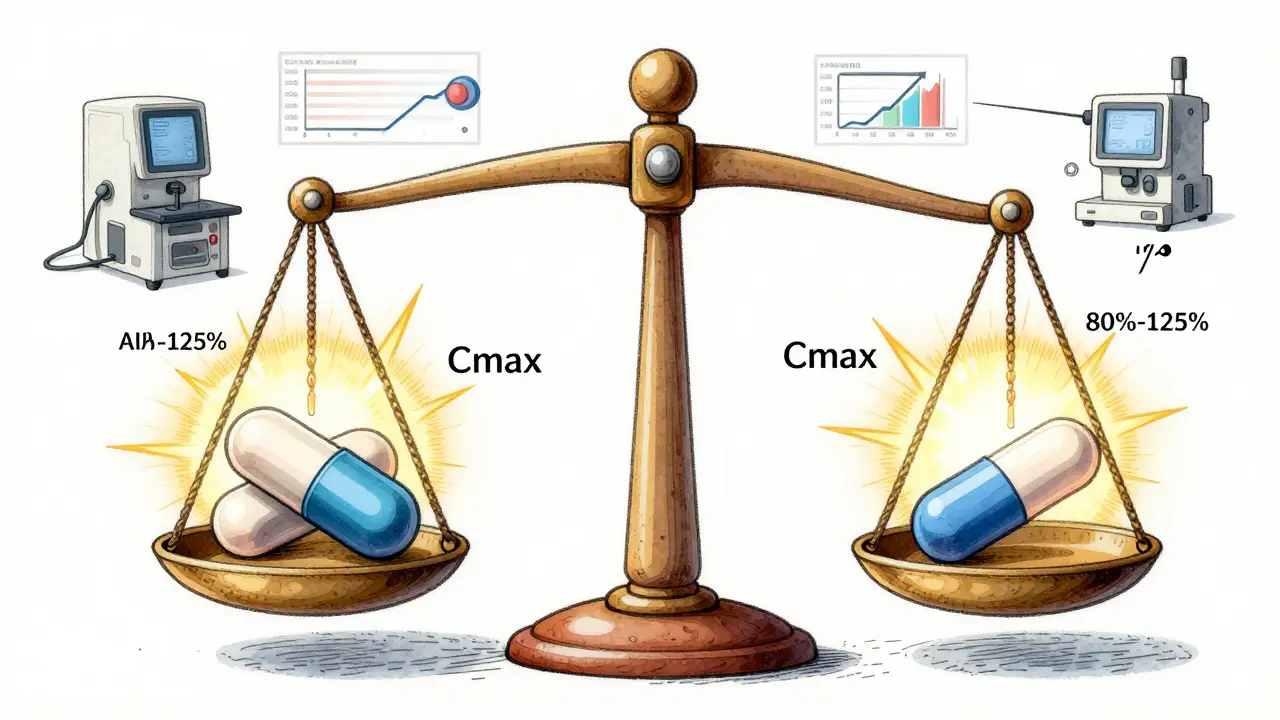

The 80%-125% Rule: Why It Exists

Here’s the rule every generic drug must pass: the 90% confidence interval for both Cmax and AUC must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s values.

That means if the brand drug’s AUC is 100 mg·h/L, the generic’s must be between 80 and 125 mg·h/L. Same for Cmax. It’s not about being identical-it’s about being close enough that no meaningful difference in effect or safety occurs.

This range didn’t come from a guess. It came from decades of data and statistical analysis. In the 1990s, regulators realized that a 20% difference in exposure was rarely clinically significant for most drugs. But they also knew that drug levels vary naturally between people. So they used logarithmic scales to handle the fact that drug concentrations follow a log-normal pattern-not a straight line. That’s why the math works on a log scale: ln(0.8) = -0.2231 and ln(1.25) = 0.2231. Symmetrical. Clean. Proven.

And here’s the kicker: both Cmax and AUC must pass. One alone isn’t enough. A drug could have perfect AUC but a wildly different Cmax-and still be unsafe. Or vice versa. That’s why regulators require both. It’s a double-check.

When the Rules Get Tighter

Not all drugs play by the same rules. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where small changes can cause big problems-the 80%-125% range is too loose.

Take warfarin. A 10% drop in exposure might mean a clot. A 10% rise could mean bleeding. That’s why the EMA recommends tighter limits: 90% to 111% for certain drugs. The FDA is moving in the same direction, especially for levothyroxine, digoxin, and cyclosporine.

Then there’s the problem of high variability. Some drugs behave differently in different people. One person’s blood level might swing 40% from day to day, even with the same dose. For those, the standard bioequivalence test can unfairly block good generics. That’s why the EMA allows something called scaled average bioequivalence. It adjusts the acceptance range based on how much the drug varies in the body. The FDA allows it too-but only for a few specific drugs, and only after heavy scrutiny.

These exceptions prove the rule: the system isn’t rigid. It adapts when the science says so.

How Studies Are Done (And Why They Sometimes Fail)

Most bioequivalence studies involve 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They take the brand drug one day, then the generic another, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours. That’s a lot of needles-but it’s the only way to map the curve accurately.

Here’s where things go wrong: poor sampling. If you don’t take blood samples often enough in the first hour or two, you might miss the true Cmax. A study from 2020 found that 15% of failed bioequivalence trials were due to this mistake. Another common issue? Using nominal times instead of actual times. If a sample was supposed to be taken at 1 hour but was actually drawn at 1 hour and 12 minutes, you have to use the real time-not the planned one. Otherwise, your curve is wrong.

And the math? It’s not simple averages. You have to log-transform the data first. AUC and Cmax aren’t normally distributed-they’re skewed. If you treat them like regular numbers, your stats are garbage. That’s why every lab uses software like Phoenix WinNonlin. It’s the industry standard. It handles the logs, the confidence intervals, the crossover design-all automatically.

Why This System Works (And Why It’s Here to Stay)

Over 1,200 generic drugs were approved in the U.S. in 2022. Almost all relied on Cmax and AUC. And here’s the proof it works: a 2019 review of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs-when they passed bioequivalence.

This system saved billions. Imagine if every generic drug needed a new clinical trial proving it reduced heart attacks or cured infections. It would take years. It would cost millions. And generics wouldn’t be affordable.

Regulators didn’t invent this out of thin air. It’s built on 50 years of pharmacokinetic research-from Leslie Benet’s early work in the 1970s to today’s LC-MS/MS machines that can detect a drug at 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s a billionth of a gram. Enough to measure even the tiniest doses.

Even as new tech emerges-like computer modeling to predict exposure instead of drawing blood-the core metrics stay. Why? Because they’ve been tested in millions of patients. Because they’re simple to measure. Because they’re proven.

Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA put it plainly at a 2022 conference: “AUC and Cmax will remain the primary bioequivalence endpoints for conventional drug products for the foreseeable future.” He’s not just being conservative. He’s being honest.

What This Means for You

If you take a generic drug, you’re not taking a cheaper version. You’re taking a scientifically verified copy. The same active ingredient. The same dose. The same absorption profile-within strict, evidence-based limits.

It’s not magic. It’s math. It’s blood samples. It’s decades of careful science. And it’s why you can trust your prescription, no matter which bottle you pick up.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level of a drug found in your bloodstream after taking a dose. In bioequivalence studies, it measures how quickly a drug is absorbed. If the generic drug’s Cmax is too low or too high compared to the brand, it could mean slower relief or increased side effects. Regulators require it to be within 80%-125% of the original drug’s value.

What does AUC mean in bioequivalence?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It’s calculated by plotting blood concentration levels from the moment the drug is taken until it’s mostly cleared. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body actually absorbed. For most medications, this is more important than how fast it peaks. The generic’s AUC must fall within 80%-125% of the brand’s to be considered bioequivalent.

Why do both Cmax and AUC need to pass for bioequivalence?

Because they measure different things. Cmax tells you about the rate of absorption-how fast the drug enters your system. AUC tells you about the extent of absorption-how much of the drug gets in overall. A drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but reach peak levels too slowly or too quickly (Cmax), which could affect safety or effectiveness. Regulators require both to pass to ensure the generic behaves just like the original in real-world use.

Why is the bioequivalence range 80%-125%?

This range was established based on statistical analysis of decades of clinical data. A 20% difference in exposure (either way) has been shown to rarely cause clinically meaningful differences in effect or safety for most drugs. The range is symmetrical on a logarithmic scale, which fits how drug concentrations naturally vary in the body. It’s not arbitrary-it’s grounded in real-world evidence and approved by global regulators since the 1990s.

Are there drugs that need stricter bioequivalence limits?

Yes. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and digoxin-require tighter limits, often 90%-111%. Small changes in exposure for these drugs can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure. Regulatory agencies like the EMA and FDA have updated their guidelines to reflect this, allowing for scaled bioequivalence or stricter criteria for these high-risk medications.

Can a generic drug fail bioequivalence even if it’s the same ingredient?

Absolutely. Two drugs can have the same active ingredient but different inactive ingredients (fillers, coatings, etc.), which affect how quickly the drug dissolves or is absorbed. A generic might release too slowly, too quickly, or unevenly. That’s why bioequivalence testing is required-not just chemical analysis. Even a tiny difference in formulation can cause Cmax or AUC to fall outside the 80%-125% range, leading to rejection.

How accurate are bioequivalence studies?

Highly accurate when done properly. Modern labs use LC-MS/MS technology to detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. Studies follow strict protocols with 12-18 blood draws per subject and validated software for analysis. The failure rate is low-around 5-10%-and most failures are due to poor sampling timing or small sample sizes, not poor formulation. When a study passes, you can trust the result.

What Comes Next?

The future of bioequivalence isn’t about replacing Cmax and AUC-it’s about adding layers. For complex drugs like extended-release tablets or inhalers, regulators are exploring partial AUC (measuring exposure only during key time windows) or modeling to predict exposure without dozens of blood draws.

But for now, if you’re taking a standard tablet or capsule, the system works. Cmax and AUC are the gatekeepers. They’re the reason you can switch from brand to generic without wondering if it’ll work. And that’s not just science-it’s public health.

So basically, we’re trusting math over millions of people’s lived experience? Cool. I’ve seen generics that just… don’t work. Like, at all. And no, I’m not crazy. I’ve switched back and forth. The numbers don’t lie, but bodies do. And sometimes, bodies remember.

This is so important to understand! 💖 Every time someone chooses a generic, they’re choosing affordability, access, and science-all at once. Thank you for breaking this down so clearly. We should celebrate this kind of quiet innovation every day. 🌍💊

AMERICA MADE THIS SYSTEM. 🇺🇸 The FDA didn’t just ‘borrow’ it-they perfected it. Meanwhile, other countries are still trying to figure out how to spell ‘bioequivalence.’ 😤 Who gave the EMA permission to tighten the range? We built the bridge. Don’t you dare tweak the rails without asking first.

Let’s be precise: Cmax reflects the rate-limiting step of absorption, typically governed by dissolution kinetics and membrane permeability, whereas AUC is a composite metric integrating bioavailability, first-pass metabolism, and elimination half-life. The 80–125% CI is derived from log-normal distribution assumptions under a two-sequence, two-period crossover design with sufficient power (≥80%) to detect clinically irrelevant differences. If your lab uses arithmetic means instead of geometric means post-log-transformation, your entire study is invalidated.

Actually, the log-transformation isn’t just for convenience-it’s mandatory under ICH E9 and E14 guidelines because pharmacokinetic data is inherently multiplicative, not additive. And if you’re not using a mixed-effects model for crossover designs with random subject effects, you’re doing it wrong. Also, most people don’t realize that the 90% CI is calculated on the log scale, then back-transformed. It’s not a 20% window-it’s a geometric mean ratio with symmetric log-space boundaries. If you think it’s arbitrary, you haven’t read the 1992 FDA guidance.

You know, I just want to say-this whole thing? It’s beautiful. Think about it: people all over the world, in villages and cities, in places with no fancy hospitals, are getting life-saving meds because some scientist in the ‘90s said, ‘Hey, let’s just measure the curve’-and then they built a whole system around it. No drama. No hype. Just math, blood, and trust. And now, someone in India can take a pill that’s just as good as the one in Boston, and it doesn’t cost a fortune. That’s not just science-that’s humanity, right there. I’m tearing up a little. 🥹

lol at the people who think generics are ‘fake’… you know the brand name drug was made in the same factory as the generic, right? Same machine, same chemist, same batch code sometimes. The only difference? The label. And the price. And the fact that you’re not paying for a 300% markup on marketing. 🤷♂️

Wait-so you’re telling me that a drug company can change the coating, the filler, the particle size, the manufacturing process, the solvent used in crystallization, and the drying temperature-and as long as Cmax and AUC are within 80–125%, it’s considered ‘bioequivalent’? But if the tablet crumbles in your hand, or if it tastes like cardboard, or if it gives you a headache because of the magnesium stearate? Doesn’t matter? That’s not science-that’s a loophole dressed up as a standard. And don’t even get me started on the ‘washout period’-how many people actually follow it? I’ve seen studies where subjects skipped the washout and the lab just ‘adjusted’ the data. This system is held together by duct tape and hope.

As someone from India, I have seen both branded and generic versions of the same drug. The difference in price is 10x. The difference in effect? None. The science works. The system works. Do not let fear or misinformation replace evidence. This is not a Western invention-it is a global standard that saves lives in rural clinics every day.

Wow. So we’re just supposed to believe that a 20% variation is ‘clinically irrelevant’? That’s like saying a 20% variation in your insulin dose doesn’t matter. Or your blood pressure meds. Or your chemo. This is the kind of thinking that gets people killed. The FDA is not a saint. They’re a bureaucracy that got lazy. And now we’re all paying for it-with our health.

Actually, your entire premise is flawed. You’re assuming Cmax and AUC are the only metrics that matter. But what about the distribution volume? Clearance? Half-life? What about inter-individual variability in CYP enzymes? You’re reducing a complex pharmacokinetic profile to two numbers and calling it ‘science.’ Meanwhile, the real world is full of polymorphic metabolizers, gut microbiomes, and drug-food interactions that these studies completely ignore. You’re not proving bioequivalence-you’re proving statistical compliance. Big difference.