Boxed Warning Changes: How to Track FDA Label Updates Over Time

Boxed Warning Change Timeline

Enter a drug name to see its boxed warning history

When a drug carries a boxed warning, it’s not just another footnote on the label. It’s the FDA’s loudest alarm bell - a black-bordered, bold-uppercase alert that tells doctors and patients: this medicine can kill you. These warnings don’t appear by accident. They’re the result of years of hidden harm, delayed data, and real patient deaths. And they change. Often. If you’re prescribing, dispensing, or taking these drugs, you need to know how to track those changes - because the warning you read last year might be outdated, expanded, or even removed today.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning, also called a black box warning (BBW), is the strongest safety alert the U.S. Food and Drug Administration can require on a prescription drug label. It’s placed at the very top of the prescribing information, before even contraindications or general warnings. The text is surrounded by a thick black border, written in bullet points, and headed with bold, all-caps letters like “WARNING: SUICIDAL THINKING” or “WARNING: RISK OF DEATH.” It’s not just a reminder. It’s a legal requirement. Under 21 CFR 201.57(e), the FDA mandates this format to ensure it can’t be missed. These warnings are reserved for risks that have caused death or serious injury - not theoretical concerns, not mild side effects. Think: liver failure, heart attacks, suicidal behavior, fatal infections, or sudden death in otherwise healthy people. Since 1979, when the FDA first introduced the format, over 1,800 safety labeling changes have been recorded. Of those, 147 new boxed warnings were added between 2016 and 2023 alone. About 40% of all prescription drugs in the U.S. carry at least one. In some areas, it’s nearly universal: 87% of antipsychotics, 78% of blood thinners, and 63% of diabetes drugs have them.Why Do Boxed Warnings Change?

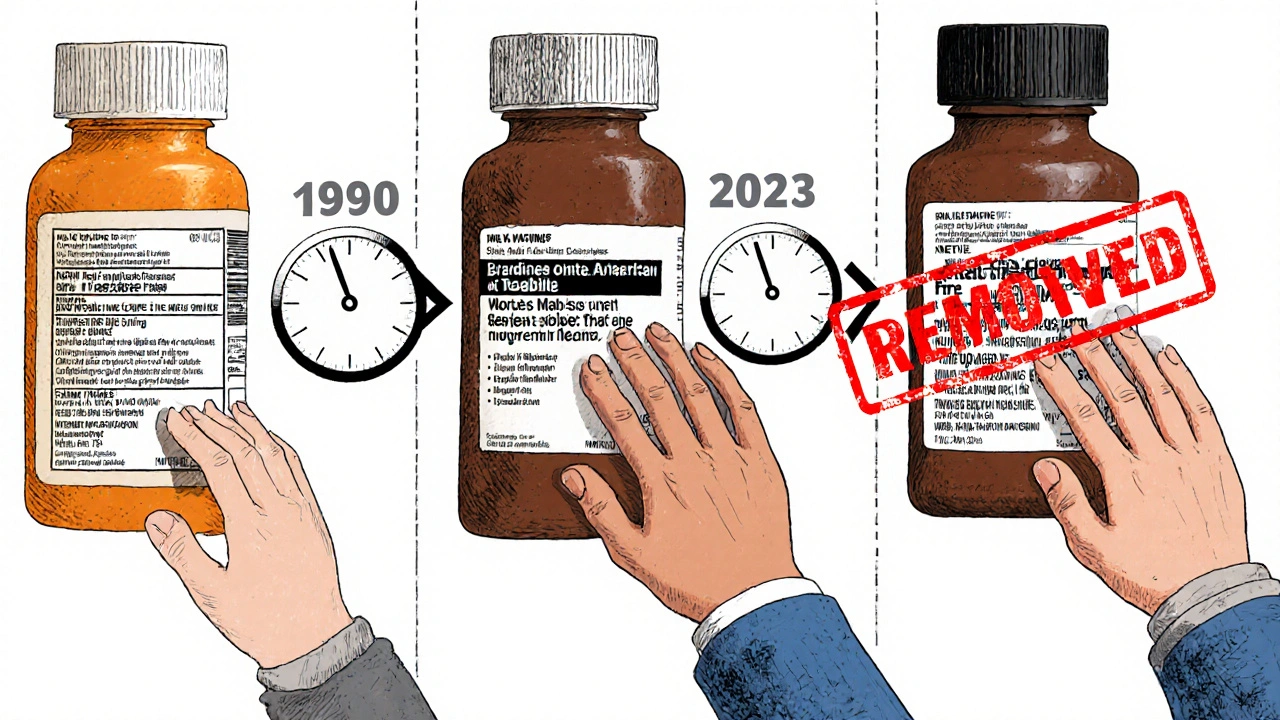

The system wasn’t designed to be perfect. It was designed to react - and it often reacts too late. Most boxed warnings don’t come from clinical trials. They come from real-world use. A drug gets approved based on a few thousand patients over months. But once it’s on the market, millions take it. Over years. And hidden risks emerge. Take fluoroquinolone antibiotics like Cipro. In 2008, the FDA added a boxed warning for tendon rupture after reports piled up from emergency rooms across the country. By then, the drug had been on the market for over 30 years. Thousands had already been injured. Or Chantix, the smoking cessation drug. In 2009, a boxed warning was added for suicidal thoughts and behavior. Prescriptions dropped by 40% overnight. But in 2016, after more data came in, the FDA removed it. Why? Because follow-up studies showed the risk wasn’t higher than quitting smoking cold turkey. The warning had been too broad, too scary - and it kept people from a life-saving tool. Changes happen in three ways:- New warnings (29% of updates): Something never seen before - like the 2023 warning for Aduhelm causing brain swelling.

- Major updates (32%): The warning gets expanded. Maybe it now includes a new population at risk, like pregnant women or seniors.

- Minor updates (40%): Clarifications, grammar tweaks, or added context - but still important.

Where to Find Updated Boxed Warnings

The FDA doesn’t send out emails. You won’t get a notice in your mailbox. You have to go looking. The only official, searchable, up-to-date source is the Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database. Launched in January 2016, it tracks every change to drug labels since then - including boxed warnings, contraindications, and new precautions. Here’s how to use it:- Go to the FDA’s SrLC database website.

- Search by drug name, active ingredient, or even the specific warning section (e.g., “BOXED WARNING”).

- Filter by date range - especially useful if you’re checking for changes since your last review.

- Click on a record. Each entry includes the exact text added or modified, the date of change, and the reason (e.g., “post-marketing reports of hepatotoxicity”).

How Clinicians Miss Updates (And Why It Matters)

You’d think doctors and pharmacists are on top of this. But they’re not. In a 2017 FDA survey of 500 providers, 87% said they always check for boxed warnings when prescribing. But 63% admitted they sometimes overlook updates to existing warnings. Why? Three reasons:- Information overload: With over 1,800 labeling changes since 2016, it’s impossible to remember them all.

- Fragmented systems: EHRs don’t always sync with FDA updates. Alerts might be buried in a notification feed.

- False alarms: Many hospital systems use automated alerts. But 41% of pharmacies say these generate too many false positives - so they start ignoring them.

Industry Response and the Push for Change

The pharmaceutical industry spends $2.8 billion a year on risk management systems - largely because of boxed warnings. Specialty pharmacies that use automated tracking systems report 27% fewer medication-related adverse events. Community pharmacies? Only 38% have formal monitoring in place. The FDA knows the system is broken. In 2023, they announced a plan to modernize the boxed warning format by 2026. Pilot tests are already underway: testing color-coded alerts, icons, and digital-only versions for EHRs. The goal? Make warnings easier to understand - not just harder to ignore. Critics aren’t satisfied. Dr. Jerry Avorn of Harvard says we need a tiered warning system - one that distinguishes between “possible risk” and “proven danger.” Others argue the system is too slow. The FDA’s own Sentinel Initiative, a $150 million project launched in 2008, has cut the time to detect safety signals by over two years - but it still takes years to turn that signal into a label change. The most promising development? A $25 million partnership between the FDA and the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) consortium. They’re building tools to use real-time data from millions of electronic health records. The goal? Reduce the median time from risk detection to warning update - from 11 years to under 5.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you’re a prescriber, pharmacist, or patient:- Check the SrLC database monthly - especially for drugs you use often. Set a calendar reminder.

- Don’t assume a warning is permanent. Chantix’s warning was removed. Others have been narrowed. Always verify.

- Ask for a Medication Guide when a new boxed warning is added. It’s your right - and it improves understanding.

- Use automated alerts wisely. If your system floods you with alerts, talk to your pharmacy or hospital IT. Tune them. Filter them.

- Know your drugs. Antipsychotics, anticoagulants, and diabetes meds are the most likely to carry boxed warnings. Be extra vigilant.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are boxed warnings the same as black box warnings?

Yes. "Boxed warning" and "black box warning" (BBW) are used interchangeably. The term "black box" comes from the thick black border that surrounds the warning text on drug labels. The FDA officially calls it a "boxed warning," but both terms refer to the same regulatory alert.

Can a boxed warning be removed?

Yes. The FDA can remove or modify a boxed warning if new evidence shows the risk is lower than originally thought, or if the warning was based on incomplete data. For example, the boxed warning for Chantix (varenicline) related to suicidal behavior was removed in 2016 after follow-up studies found no increased risk compared to quitting smoking without medication.

How often are boxed warnings updated?

Between 2008 and 2015, the FDA issued an average of 15 new or updated boxed warnings per year. Since 2016, over 147 new boxed warnings have been added through 2023, with major updates occurring regularly. Updates happen whenever new safety data emerges - sometimes within months of a drug’s approval, sometimes decades later.

Do all countries use boxed warnings?

No. The U.S. FDA is the only agency that uses the formal black-bordered boxed warning. The European Medicines Agency uses a "black triangle" symbol (▼) to mark newly approved drugs under additional monitoring, but it doesn’t have an equivalent to the U.S. boxed warning. Other countries may issue safety alerts, but none use the same standardized, legally mandated format.

Why do some doctors ignore boxed warnings?

Some doctors feel boxed warnings are overly cautious or outdated. For example, the warning for Avandia (rosiglitazone) on cardiovascular risk led many to stop prescribing it - even though later studies questioned the strength of that link. Others are overwhelmed by the volume of alerts, especially when automated systems generate too many false positives. A 2023 Medscape poll found 52% of physicians believe some warnings discourage use of beneficial drugs.

How can patients find out if a drug’s boxed warning changed?

Patients should ask their pharmacist or prescriber directly. The FDA doesn’t notify patients directly. However, if a boxed warning changes, the drug’s prescribing information is updated, and the Medication Guide (if provided) should be revised. Patients can also check the FDA’s SrLC database using the drug’s generic name, but it’s designed for professionals. The easiest route is to ask your healthcare provider: "Has anything changed about this drug’s safety warning?"

So you're telling me I need to check a government database every month just to not kill my patients? Cool.

I once prescribed a drug with a boxed warning and didn't check the update. Three months later, the patient ended up in the ICU. The warning had been expanded to include their exact condition. They didn't die, but I'll never forget the look on their face when I admitted I didn't know. Now I check the SrLC every Sunday morning like it's church. No excuses.

Why does the FDA even bother with text warnings if no one reads them? Why not just make the EHR scream when you try to prescribe?

For anyone using EHRs: I built a custom alert script that pulls from the SrLC API and pushes a daily digest to our pharmacy team. It’s not perfect, but it cut our missed updates by 70%. DM me if you want the template. Seriously - it saved us from a potential disaster last year with a blood thinner update.

Let’s be honest: the FDA’s entire system is a theater of compliance. They slap on a black box like it’s a magic shield-then sit back while clinicians drown in 1,800+ updates, automated alerts that lie, and Medication Guides that no one prints. And we wonder why people die? It’s not the drugs-it’s the bureaucracy that treats safety like a checkbox.

As someone who works in a community pharmacy in rural India, I can tell you this problem is global, not just American. We don’t even have access to the SrLC database. We rely on drug reps, outdated pamphlets, and what the hospital sends us. Sometimes, we don’t know about a boxed warning until a patient comes in with a reaction and we have to Google it. The FDA’s system is brilliant-but it’s built for a world that doesn’t exist outside of urban U.S. hospitals. We need decentralized, low-bandwidth alerts. Maybe SMS-based? Or WhatsApp? Imagine a simple text: "Cipro - new warning: tendon rupture risk now includes patients over 60." That’s all we need.

The notion that clinicians "ignore" boxed warnings is a dangerous oversimplification. The issue isn’t negligence-it’s systemic failure. When a provider is expected to process hundreds of dynamic, non-standardized alerts across fragmented platforms, cognitive overload is inevitable. The solution is not more vigilance-it’s better design. Standardized, machine-readable label updates integrated directly into clinical decision support systems, with tiered severity flags and auto-archived change logs. Until then, we are asking humans to do the job of a poorly coded algorithm.

Everyone’s talking about the SrLC database like it’s the holy grail-but did you know it doesn’t even track changes to the "Minor Updates" category in a way that’s searchable? You have to manually compare PDFs from Drugs@FDA. And good luck finding the original warning text from 2012. The FDA doesn’t archive versions properly. This whole system is a house of cards built on legacy tech. I’ve spent weeks trying to trace one warning change. It’s not a database-it’s a digital graveyard.

Why are we even letting Big Pharma get away with this? They push drugs through approval with barely any data, then sit on adverse event reports for years. The FDA’s 11-year median to issue a warning? That’s not slow-it’s complicity. And now they want to "modernize" with color-coded alerts? Please. Fix the root problem: make drug companies fund real-time post-market surveillance. Make them pay for the data. Not the taxpayer.

Chantix’s warning being removed is the most telling thing here. The FDA added it because of panic. Removed it because of data. That’s the whole problem. They react to headlines, not science. A warning isn’t a safety tool-it’s a PR tool. And the people who pay the price? The ones who stopped taking it because they were scared, not informed.

I used to think boxed warnings were just scare tactics. Then my mom got prescribed a drug with one. She didn’t understand it. The pharmacist didn’t explain it. She stopped taking it. Six months later, she had a stroke. Turns out the warning was for a different population-but the fact that she didn’t know to ask meant she never got the right info. I don’t care about databases or APIs. I care that people understand what’s in the bottle. Maybe we need a 2-minute video for every boxed warning? Something real. Not legal jargon.

you know what’s wild? we’re all so obsessed with tracking warnings like they’re some kind of sacred text… but what if the real problem isn’t that we’re missing updates… but that we’re missing the humanity behind them? like… behind every boxed warning is someone’s uncle who died on a Tuesday because no one told him the pill could stop his heart. we’re so busy optimizing the system we forgot why it exists. maybe we need a human voice attached to every update. not just text. not just a link. a story. a name. a face. that’s how you make people care.

So… we spent $25 million to cut the warning lag from 11 years to 5… and that’s supposed to be progress? We’re still talking about a decade of people dying before we fix something we knew was broken in 2008. Congrats, FDA. You just turned tragedy into a KPI.